Six Acquisition Pathways for Large-Scale, Complex Systems

PUBLISHED IN

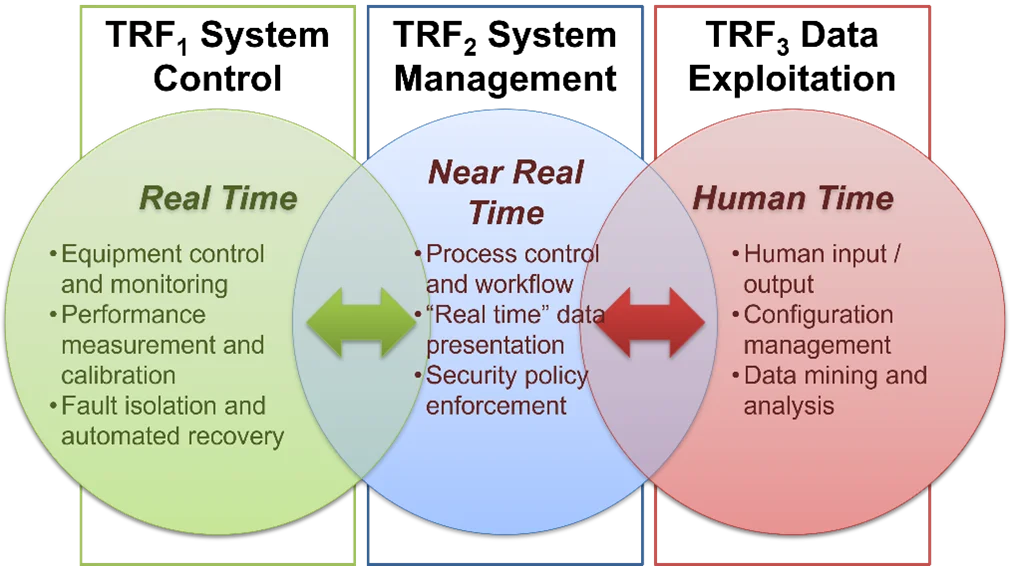

Software ArchitectureIn software acquisition as in software architecture, one size does not fit all. Complex mixed-criticality systems require a flexible government-acquisition system for approval, oversight, and funding. Our previous blog post described how technical reference frameworks (TRFs) provide flexible computing and infrastructure environments by means of modular components that align a pattern of temporal needs to scale with the processing needs for reusable domain architectures. TRFs manage the full range of military capabilities, juxtaposing the boundaries of criticality and scale. In this post we show how to map TRFs to the different pathways that compose the DoD’s Adaptive Acquisition Framework (AAF).

Acquisition Flexibility

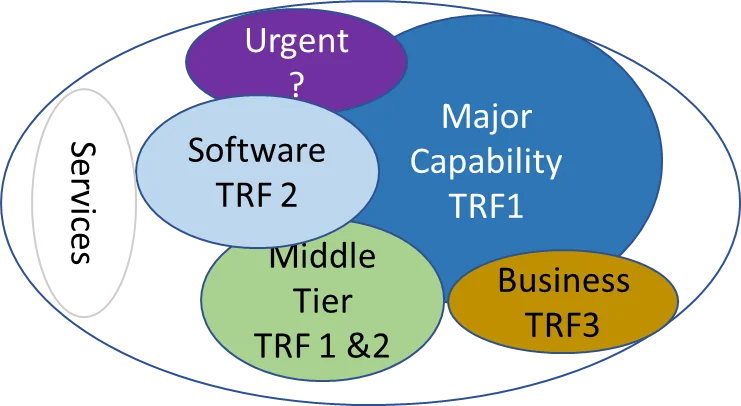

Complex architectures of architectures comprising functions of mixed criticality require a blending of different TRFs. As shown in Figure 1, a single, unified acquisition strategy that would also apply a unified technical architecture for such a system of systems (referred to henceforth more compactly as “systems”) would install artificial processes and boundaries for developing, securing, operating, and improving those systems.

Just as TRFs are tuned and optimized for the different scales in which these systems operate, the strategies and practices for acquiring these systems must be similarly tuned and optimized. In response to this need, the DoD introduced the Adaptive Acquisition Framework (AAF) to instantiate flexibility and agility as foundational elements for product development and lifecycle management across all acquisition programs. The AAF can be pursued effectively by enveloping the DoD Digital Engineering Strategy, thereby putting the right tools into the right places for the product being pursued. This approach further helps the acquisition community manage unique capability needs and risk profiles while encouraging customization.

To limit complexity and decrease risk, program executive officers and program managers traditionally apply an acquisition strategy that self-limits the available options. These acquisition practices ignore the cadence, requirements, and risk profile that uniquely characterize the types of components or subsystems being created, and instead apply a common schedule-driven cadence and main-event-like mandatory programmatic reviews in programs that need a different approach. Tactics for dealing with technical complexity and future delivery needs of innovation can be introduced over time, but at an appropriate pace for the target technology, program requirements, schedule, and budget.

The TRFs applied in mixed-criticality systems should therefore be structured to handle layering-on those downstream features and deploying them in risk-prudent methods that are responsive to the warfighter needs while addressing appropriate safety/security concerns. Fortunately, the AAF allows programs to compose the approach in ways that best match the technology and use case of the different parts of the acquisition in the most efficient manner. It affords considerable flexibility to decision authorities and programs regarding acquisition strategy, governance instruments, and overall execution of the program.

Specifically, DoDI 5000.02, Section 3.1 charges decision authorities with

- tailoring of program strategies and oversight

- timing and scope of decision reviews

- phasing of capability content over time

- pathway selection and adaptation (see Figure 4 below)

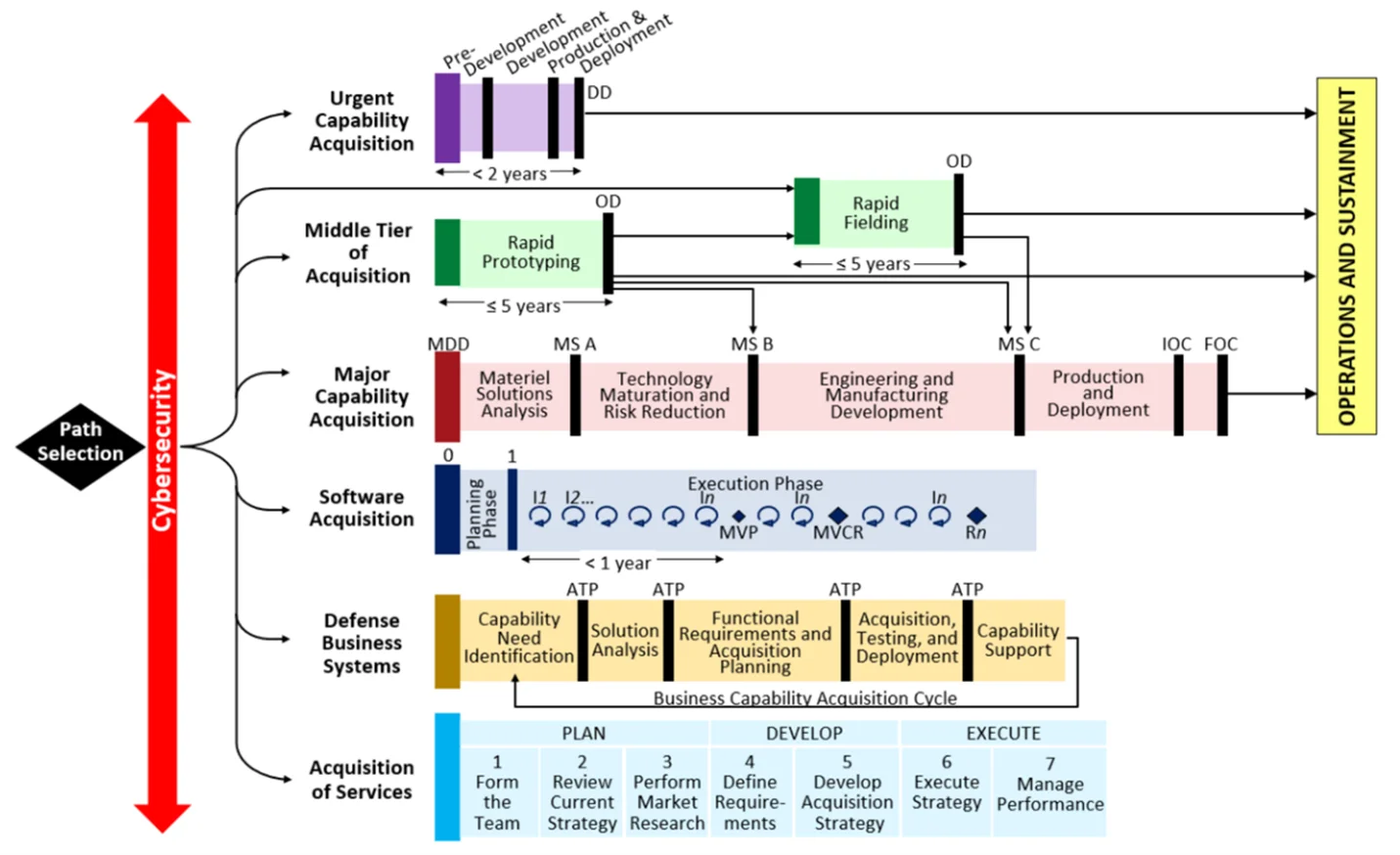

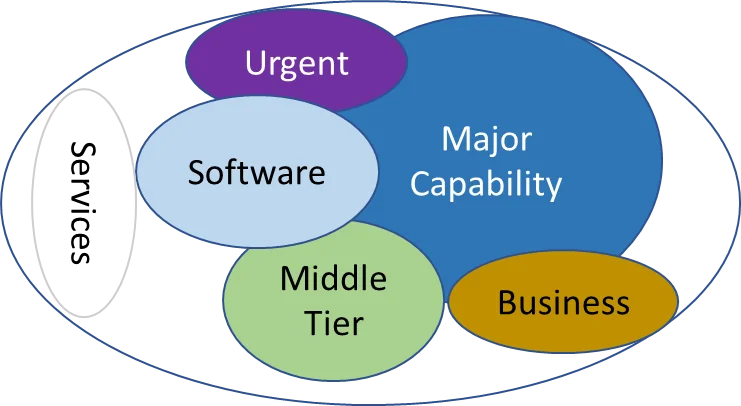

Through this acquisition reform, DoD empowers the professionals doing the work with engineering the constructs, governance, and processes that enable successful achievement of program objectives. Recognizing that requirements and risk profiles are unique to each program and therefore require different acquisition strategies for one major capability acquisition (MCA), the DoD created six pathways, shown in Figure 2 below, aimed at streamlining and reducing the risk associated with the acquisition of IT systems, products, and services.

The flexibility and guidance provided by DoD 5000.02 offers options to explore multiple pathways to match the acquisition strategy to program needs. It enables acquirers to provide tailored support for the program’s unique characteristics and risk profile.

Of the six pathways, both the Software Acquisition and Defense Business Systems pathways present opportunities to explore the application of TRFs. Software systems, including either weapon or business systems, need to use TRFs appropriate to the technical domain being addressed. These choices make it possible for the program to achieve its objectives by leveraging environments that can be applied to their needs, instead of creating their own environment(s) each time.

Software Acquisition Pathway

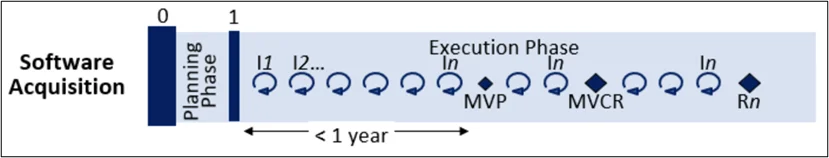

Of particular interest, the Software Acquisition pathway, enlarged in Figure 3 below, enables a program office to define an acquisition strategy that leverages current software-delivery frameworks and introduces flexibility into planning and execution. This pathway encourages software-development practices, such as Agile, DevOps, DevSecOps, and Lean, and gives a program the agility to explore cutting-edge development techniques and technologies. Through the iterative nature of the pathway, disclosure on the characteristics of the design gets to stakeholders early and often. Stakeholders and vendors communicate throughout design and development with the government, providing input and gaining clarification as appropriate.

In short, the Software Acquisition pathway

- enables continuous integration and delivery of software capability on timelines acceptable to the warfighter and end user, or mission requirement

- is the preferred path for acquisition and development of software-intensive systems

- establishes business-decision artifacts to manage risk and enable successful software acquisition and development

The Software Acquisition pathway is appropriate for military-unique capabilities, such as real-time command-and-control functionality, where the design is focused on custom-built or highly customized software. The use of TRFs 1 and 2 may be well suited for these systems.

However, the Software Acquisition pathway is likely not appropriate for buying business systems that are made up largely of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) products with some minor alterations or code-only improvements (more on this later).

Additional Pathways for Consideration

Urgent Capability Acquisition

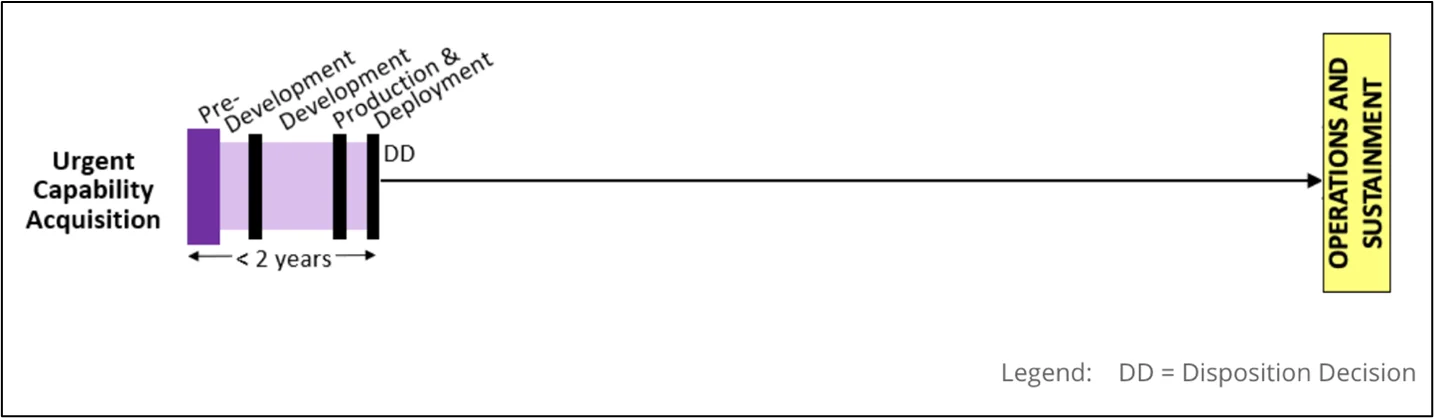

The Urgent Capability Acquisition pathway, enlarged in Figure 4 below, is reserved for capabilities required to save lives or ascertain mission accomplishment. This pathway employs a Lean acquisition process that fields capabilities fulfilling urgent existing or emerging operational needs or quick reactions in less than two years.

Diverse types of products can be fielded as an urgent capability. It is therefore hard to assert the use of a specific TRF for this type of acquisition, though TRFs 1 and 2 may be suitable. One advantage of using these frameworks in rapid capability acquisition is that the effort to establish and manage the development and deployment environment can be leveraged across many programs, releasing resources to focus on the uniquely needed military capability. It would likely also help scale the productionization of an urgent capability if its utility is proven especially valuable in the warfighting arena.

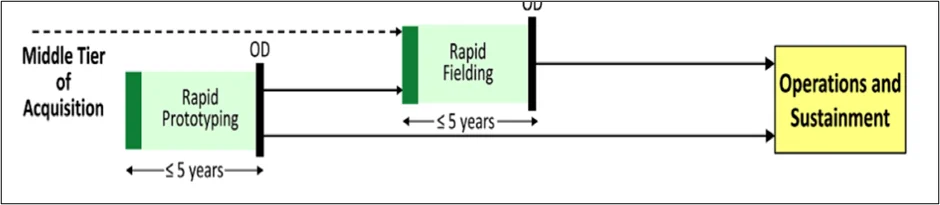

Middle Tier of Acquisition

The Middle Tier of Acquisition (MTA) pathway, enlarged in Figure 5 below, is used to rapidly develop fieldable prototypes within an acquisition program to demonstrate new capabilities or rapidly field production quantities of systems with proven technologies that require minimal development. The MTA pathway is intended to fill a gap in the defense acquisition system for those capabilities with a level of maturity that enables rapid prototyping within an acquisition program or fielded within five years of the MTA program start. The MTA pathway can be used to accelerate capability maturation before transitioning to another acquisition pathway or to minimally develop a capability before rapidly fielding.

The rapid-prototyping path provides for the use of innovative technologies and new capabilities to rapidly develop fieldable prototypes to demonstrate new capabilities and meet emerging military needs. The objectives of an acquisition program under this path involve fielding a prototype that was successfully demonstrated in an operational environment and to provide a residual operational capability within five years of the program start date. Virtual-prototyping models are acceptable if they yield a fieldable residual operational capability. MTA programs may not be planned to exceed five years to completion and, in execution, will not exceed five years after MTA program start without a defense acquisition executive (DAE) waiver.

The rapid-fielding path provides for the use of existing products and proven technologies to field production quantities of new or upgraded systems with minimal development required. The objective of an acquisition program under this path is to begin production within six months and complete fielding within five years of the MTA program start date. The production start date of the MTA program will not exceed six months after the MTA program start date without a DAE waiver.

Similar benefits to the use of TRFs 1 and 2 in the development of urgent capabilities apply to the acquisition of middle-tier capabilities. This acquisition is particularly valuable given that middle-tier products are often productized in multiple quantities, fielded for longer periods, and subject to evolving demands for capability that could be delivered with software upgrades. TRFs 1 and 2 are particularly suitable for this environment.

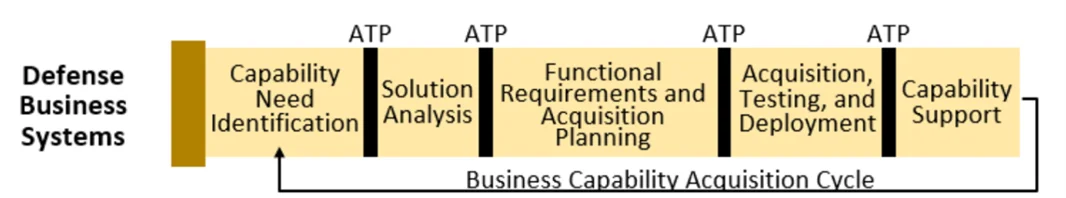

Defense Business Systems Pathway

Figure 6 shows the pathway and the cyclical Business Capability Acquisition Cycle. The authority to proceed (ATP) gates compartmentalize the phases, and the process reduces much of the paperwork required in DoDI 5000.02. Details regarding the execution of the pathway can be found at https://aaf.dau.edu/aaf/dbs/. The pathway depends on continuous process improvement and could be leveraged as a streamlined path for acquiring components that are commercially available.

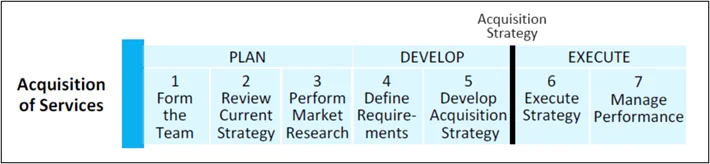

Acquisition of Services

This pathway, enlarged in Figure 7 below, is intended to identify the required services, research the potential contractors, contract for the services, and manage performance. The pathway activities are broken into three phases: plan, develop, and execute. This pathway is described in the DoD Handbook for the Training and Development of the Services Acquisition Workforce.

Major Capability Acquisition

A Major Capability Acquisition (MCA) pathway acquires and modernizes military-unique programs that provide enduring capability. It is hard to conceive of any MCA that would not be software-reliant. Should that be the case, a blended approach to the authorities of the various acquisition pathways would fit the best framework to the business needs of the program such as shown in Figure 8. Matching industry incentives and business models can be tuned to the type of activity, resources, and cadence of action. Overall execution risk would be reduced by combining these policies in a coordinated fashion.

As previously described, there is a correlation between acquisition pathways and TRFs. Figure 9 presents a mapping of how those could be applied. Major capabilities would, in many cases, be tied to a specific military platform (sea-going, land-based, flight vehicle, spacecraft, etc.). These vehicles will require real-time control systems for which TFR 1 is best suited. In addition, the platform-level integration of systems and subsystems can be derived from cross-platform product lines. The application of those products into new major capabilities would provide the propelling need to transition into TRFs to reduce execution and integration risk for the overall enterprise. Those military-unique capabilities developed under the Middle Tier or Software Acquisition pathways could be built on TRFs 1, 2, and 3.

Establishing development and deployment environments for capability, as well as the modeling and facilities used to support development testing, operational testing, and lifecycle support services could be acquired under a combination of the Acquisition of Services and Defense Business Systems pathways. Those functions would likely be best suited for the use of TRF 3.

In this post, we have shown that DoD acquisition programs no longer must go it alone and accept the burden of unbounded technical risk when it comes to building their mission systems, or the support services that they would count on. What we prescribe here is well within the realm of technical achievement today. The biggest challenge is to wrangle the structure of the acquisition environment, the funding models, and the cultural incentives.

Future Evolution of TRFs for Mixed-Criticality Systems

As the concept of TRFs gains traction and more systems are compelled to follow suit, the methods of integration, development testing, and operational testing will have to evolve as well. In addition, the methods of managing interoperability will have to evolve to address continuously evolving capability in the field, delivered on different time horizons, and to manage shifting interoperability/evolving functionality over a lifecycle of decades.

Additional Resources

Read the related post, Toward Technical Reference Frameworks to Support Large-Scale Systems of Systems.

Read the SEI blog post, Towards Affordable DoD Combat Systems in the Age of Sequestration.

Read other SEI blog posts about achieving modular open-system architectures in DoD acquisition.

Read other SEI blog posts about acquisition.

More By The Authors

More In Software Architecture

PUBLISHED IN

Software ArchitectureGet updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedMore In Software Architecture

Get updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed