Business Email Compromise: Operation Wire Wire and New Attack Vectors

In June 2018, Federal authorities announced a significant coordinated effort to disrupt business email compromise (BEC) schemes that are designed to intercept and hijack wire transfers from businesses and individuals. Operation Wire Wire, a coordinated law enforcement effort by the U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Department of the Treasury, and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, was conducted over a six-month period and resulted in 74 arrests in the United States and overseas, including 29 in Nigeria, and three in Canada, Mauritius, and Poland. The operation also resulted in the seizure of nearly $2.4 million and the disruption and recovery of approximately $14 million in fraudulent wire transfers.

In this blog post, I will review the information that can be gleaned from a close examination of Operation Wire Wire and another attack involving a Texas energy company. This post will also offer guidance on how individuals and organizations can protect themselves from these sophisticated new modes of attack.

Business Email Compromise (BEC)

Business email compromise (BEC) is the impersonation of executives or business contacts to obtain the transfer of funds or sensitive information. It targets businesses working with foreign suppliers or businesses that regularly perform wire-transfer payments. Attackers seek to intercept wire-transfer transactions so that funds are transferred to accounts that the attackers control.

Most BEC attacks include some sort of email account compromise (EAC) that targets individuals who actually perform the wire-transfer payments, typically someone other than the chief executive officer (CEO) or chief information officer (CIO). Executives, administrative assistants, attorneys, and chief information security officers (CISOs) who possess the technology to obtain sensitive information have been targeted. The attacks put business email accounts, personally identifiable information (PII), and employee wage and tax information at risk. Sectors targeted have included large retailers, energy companies, the banking industry, and real estate.

Case Study: BEC of Texas Energy Company

At the SEI CERT Division, we have worked since 2014 to help the FBI create the Cyber Investigator Certificate Program (CICP) for 750,000 law enforcement officers at federal, state, and local levels through the Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal. The following case involving an energy company in Texas is valuable as a use-case scenario for the way in which it illustrates new attack vectors.

In this case, an attacker using the pseudonym "Colvis" targeted an energy company in Texas and stole $3.2 million using a BEC scam. Colvis found employee lists on websites and posed in email as the CEO of this company, requesting that a company employee wire payment of a bogus invoice to one of the company's large vendors.

The efforts that this attacker made to make the request appear credible are instructive. He sent the spoofed email on Friday at 3:00 p.m., a common time for payments to be made and a time when many staff members have already left the office for the weekend. Colvis also exploited the tendency late on Friday afternoons for employees to feel some urgency to wrap matters up for the week.

The recipient was the CEO's assistant, whose name and email address Colvis got from the company website. The email, which was purportedly from the CEO to the assistant, had the bogus invoice attached and requested that the invoice be paid immediately. From the CEO's Facebook page, Colvis learned that the CEO coached his daughter's soccer team, and this information enabled him to include this detail in the email: "I'm going to be offline this weekend because I'll be coaching my daughter's soccer game on Sunday, so don't try to reach me then, just make sure this is done today."

The assistant wired $3.2 million to the bogus account, and Colvis ended up with about $300,000 of that money once everyone in his network--a transnational criminal organization that employs lawyers, linguists, hackers, and social engineers--had taken their cut. It took a long time for law enforcement to solve this case, which required coordination with several nations and with the internet service provider (ISP) in Romania that the network had used as a relay to avoid direct culpability when they carried out these schemes.

The FBI worked with partner agencies domestically and in multiple countries around the world in a large-scale, coordinated effort to dismantle international BEC schemes, including this one. In this case, eventually investigators located Colvis, which turned out to be the Instagram handle of a Nigerian national living in the United States. His full name is Amechi Colvis Amuegbunam, but in one of the invoices, an agent from the Secret Service was able to see a reference to "Colvis" in the PDF file, which led to the apprehension of this attacker.

This case illustrates the extent to which networks in Nigeria and elsewhere have become more sophisticated in their methods than the crude email solicitations from Nigerian princes that once proliferated on the internet. Attackers are now well trained in social engineering and the sophisticated use of a wide range of social-media applications to obtain information about targeted victims.

BEC Impact and Scope

According to the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), BEC attacks increased by 136 percent from December 2016 to May 2018. In 2017, BEC scams are estimated by the Internet Crime Report to have cost individuals and organizations $12.2 billion, ranking number one for volume of victim losses and representing nearly half of the total losses of the top 10 Internet crimes. Although figures for 2018 will not be finalized until June, the latest estimate for 2018 is $20.3 billion; so we know that costs are roughly doubling on a global scale year to year. BEC is now the number one cause of loss.

These numbers represent successful attempts by attackers to get money. As few as 1 in 100 attacks may prove productive, but the costs to attackers are low unless they are apprehended. The cost of the breach to the victim, on the other hand, exceeds the cost of the actual money transferred. In addition to the financial loss, cybercrime costs include damage and destruction of data, theft of intellectual property, theft of PII and financial data, forensic investigation time and effort, restoration and deletion of hacked data and systems, fraud, post-attack response, detection costs, and harm to the company brand. Personal victims of financial fraud feel fear regarding their personal security, as well as their physical safety.

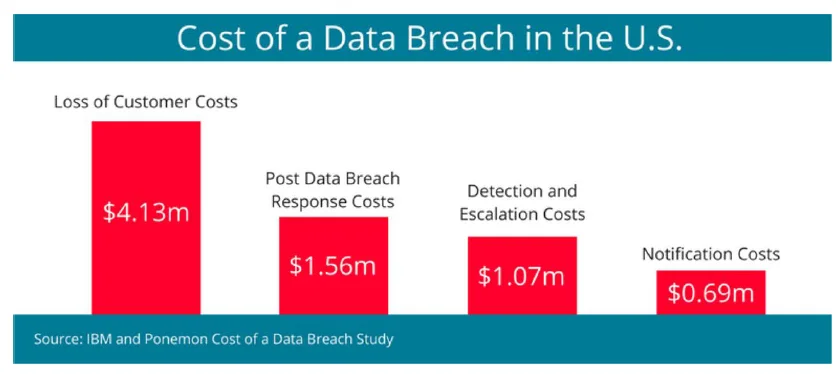

To thwart these kinds of crimes, organizations must take active measures. These measures should account for the cost of response, the cost of informing customers of widespread breaches within 72 hours as required by law, costs associated with loss of customers, and the cost of detection and escalation. Figure 1 summarizes the cost of a typical data breach in the United States.

BEC Targets and Techniques, Tactics, and Procedures (TTPs)

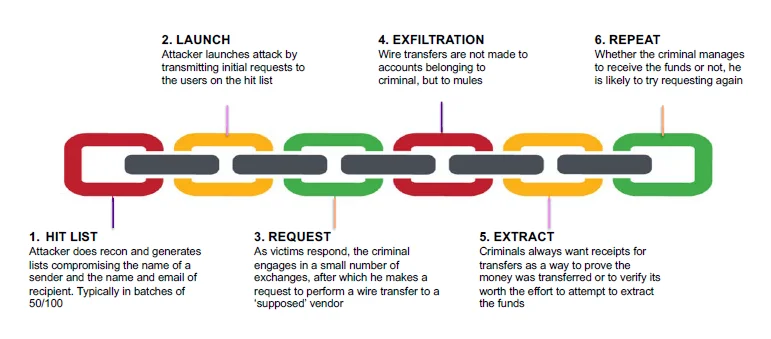

Figure 2 shows a typical pattern that characterizes the timeline of BEC attacks.

Figure 2: BEC Attack Timeline

As shown in Figure 2, attackers and their organizations initially identify targets, which are usually U.S. and European businesses that make wire transfers. They next exploit information that is available online to develop a profile on companies and their executives. They then groom the targets using various methods, including spear-phishing emails or telephone calls targeting the victim officials, usually someone in the finance department with the authority to make wire transfers. Grooming may occur over a few days or weeks, and perpetrators use persuasion techniques and pressure to manipulate and exploit human nature.

After a victim is convinced that the interaction is legitimate, the attacker then requests transfer of funds and provides wiring instructions. When the funds are wired to the attacker-controlled account, they are directed to a bank account controlled by the organized crime group. When scams are successful, these groups have well-established mechanisms for receiving money, laundering it, and transferring it so that it is hard to trace.

Operation Wire Wire

In the Operation Wire Wire case, following an investigation by the FBI and the U.S. Secret Service, 23 individuals were charged in the Southern District of Florida with laundering at least $10 million from proceeds of BEC scams. Eight defendants from the Miami area conspired to launder proceeds from numerous BEC scams, totaling at least approximately $5 million, including approximately $1.4 million from a victim corporation in Seattle, as well as various title companies and a law firm.

Money mules opened shell bank accounts in their shell company's name, and those accounts would receive wire transfers of the proceeds of various fraudulent schemes. The fraudulent schemes included many common BEC methods of attack--email hacking or spoofing and spear-phishing scams--but were supported by extensive research to make the attacks more convincing. Attackers spent significant time customizing the fraudulent email account to look like a victim's real email account. The co-conspirators would then send email messages via the hacked or spoofed email accounts to individuals or corporations, instructing them to wire large sums of money to the money mules' shell bank accounts.

The custom target lists, the extensive research, the details added to the messaging, and the investment of time creating the relationship to the victim companies have all significantly improved since the Texas energy company case just a few years earlier.

New Attack Vectors: How Attackers Collect Data on Targets

Attackers employ multiple techniques to collect data on targets. These include

- Malware--The introduction of malware into an organization's computer system enables attackers to have access to proprietary information that can help increase the credibility of the bogus request for transfer of funds.

- Spear phishing--The From, Reply to, and Sender fields in emails are spoofed to appear legitimate but are actually different from legitimate addresses in these fields.

- Social engineering--Crime rings do research on targets from publicly available information. This information is available because the target did not set up appropriate privacy settings on social-media accounts.

- Dark Web mining--Last year, 3 billion credentials were stolen and published on the Dark Web. In Operation Wire Wire, one large and well-organized 30-person attacker team created a BEC hit list based on credentials available on the Dark Web. They narrowed down the list to a little more than 200 companies that were best targets, sent malware to thousands of individuals at these companies, and conducted spear-phishing campaigns to expose these high-leverage targets. The campaign allowed the attackers to hit a group of people that was going to give them the most lucrative outcomes should their scams work.

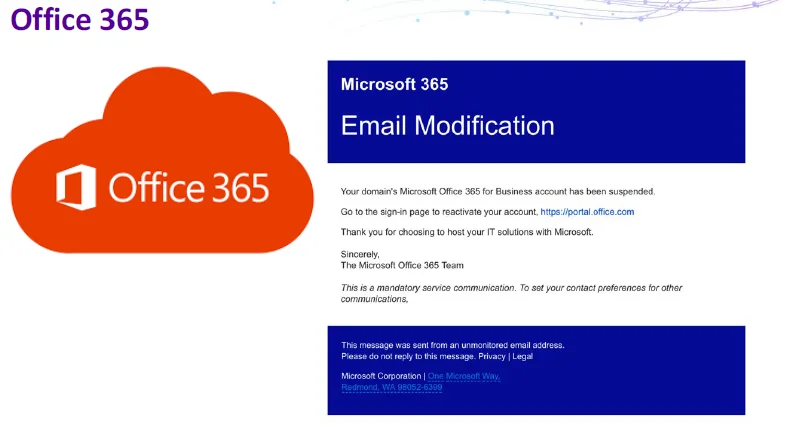

Figure 3 shows an example of a spear-phishing email message designed to get unwitting recipients to expose their login credentials to the attacker.

Figure 3: Spear-Phishing Email

The key development that is evident in a review of cases that were part of Operation Wire Wire is the increasing sophistication, organization, and variety of research methods that attackers are now using in their campaigns. The attack methods themselves have not changed much; it is the research that has changed, which is particularly true of the large group currently operating out of Nigeria. Their employees are well trained in techniques for compromising victim users, and the databases that they access in their research have user-friendly graphical user interfaces (GUIs) for accessing victims' compromised email addresses, usernames, and passwords.

From 2016 to 2017, Nigerian BEC incidents have increased 45 percent just from this particular network. The network's organizational reach has increased, and the actors themselves demonstrate increased organization and coordination. Their use of social-media platforms extends far beyond the obvious and well-known social-media platforms of Instagram and Facebook. Searches on Pipl enable an attacker to find out all the social-media platforms on which a potential victim has an account. With this information, the attacker can use multiple platforms to create a detailed case study of the victim and leverage that information in conducting scams. Attackers are now conducting research on LinkedIn, dating applications, and even FitBits--a FitBit can inform attackers that an executive is traveling and using a FitBit overseas, information that can be used to target company staff in his or her absence.

Defending Against BEC

Traditional enterprise solutions to protecting systems are of limited value in protecting against the kinds of well-crafted exploits described in this post. For example, automated detection by network appliances is powerless to prevent the willful wiring of funds to fraudulent accounts. If an attacker can get into the circle of users in an organization and persuade one user to take such an action, nothing in this transaction would trigger a network appliance to flag it. Moreover, as we have seen, the high financial reward to the attacker has motivated a wide variety of techniques for compromising individual users with access to proprietary internal information.

There are no easy answers to thwarting BEC attacks. Security training and raising user awareness are the first and last lines of defense against BEC attacks, but training time often results in lost organizational productivity, and training costs are ongoing. Awareness is key: employees must be trained to scrutinize all emails and in particular to carefully verify all vendors. For large wire transfers, it is a good idea for employees to authenticate requests for funds transfers by means of face-to-face or telephone communications with senior staff. Organizations should report all suspicious attempts to receive bogus funds transfers to the Internet Criminal Complaint Center (IC3) at https://www.ic3.gov/default.aspx.

Other steps that organizations can take include the following:

- Flag incoming email from a sender using a similar but slightly different domain name, such as abc_company vs. abc-company.

- Flag incoming email that uses a "Reply-To" address that is different from the "Sender" address.

- Create a two-step approval process for funds transfers, similar to two-factor authentication.

- Implement Sender Policy Framework (SPF), DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM), and Domain-Based Message Authentication, Reporting, and Conformance (DMARC) in the organization.

- Monitor incoming email for the use of VIP names most likely to be impersonated.

- Color code all incoming email to distinguish between internal and external accounts; this would alert recipients to instances in which an external account is attempting to spoof an internal account.

- Carefully scrutinize all email requests for transfer of funds.

Here are four key indicators of BEC to watch for that might indicate that an attack has taken place:

- Large wire or funds transfer to a recipient that the company has never dealt with in the past.

- Transfers initiated near the end of day (or cut-off windows) or before weekends or holidays.

- A receiving account that does not have a history of receiving large funds transfers in the past.

- A receiving account that is a personal account, whereas the company typically only sends wires to other businesses.

Where to Start: Strategies to Apply in Your Organization

As awareness of the BEC problem grows, law enforcement is training the state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) workforce on BEC to combat this threat.

We recommend that you apply these strategies:

- Targeted training of key financial officers for your business and corporate clients.

- Callback procedures for certain types of fund transfers.

- Training for all internal staff (account managers, personnel responsible for electronic funds transfers, security staff, wire-room staff, etc.) to identify BEC.

- Detection systems that profile both sending and receiving accounts of a funds transfer to ensure that the activity is typical for both parties.

Additional Resources

- Read the FBI description of business email compromise.

- Read the public-service announcement from the IC3 business email compromise.

- Read the U.S. Department of Justice press release about Operation Wire Wire.

- View my talk, Business Email Compromise: Operation Wire Wire and New Attack Vectors, at the 2019 RSA Conference.

More By The Author

More In Reverse Engineering for Malware Analysis

PUBLISHED IN

Get updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedMore In Reverse Engineering for Malware Analysis

Get updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed