Stop Wasting Time: Manage Time as the Limiting Resource

Lost time is never found. - Ben Franklin

Driven by a competitive marketplace, software developers and programmers are often pressured to adhere to unrealistically aggressive schedules across multiple projects. This pressure encourages management to spread the staff across all the critical work, trying to make progress everywhere at once. This trend helped to spawn the myth of the "x10 programmers"--programmers who are so much more productive than others that they will exert an outsized influence on their organizations' success or failure. Such magical thinking ignores the real problems of productivity.

In the first blog post in this series, I challenged this myth of individual programmer productivity. Rather than placing all of their focus on recruitment of the fastest programmers, I suggested that managers should help all capable programmers to become more productive. In this post I will argue that since direct work time is the limiting resource, managers exert outsized influence on productivity. Direct project time is largely under management control, so the first tool for improving programmer productivity is to maximize time available and exploit that time aggressively. I suggest some interventions that managers can use to increase the number of hours programmers spend working directly on project tasks.

Direct Work Time Might Be More Variable Than Work Speed

How many hours is a good programmer capable of spending directly on productive tasks each week? Our data from production projects show that the number of direct hours per week (time programmers spend that can be assigned to some product) is a small portion of the work week.

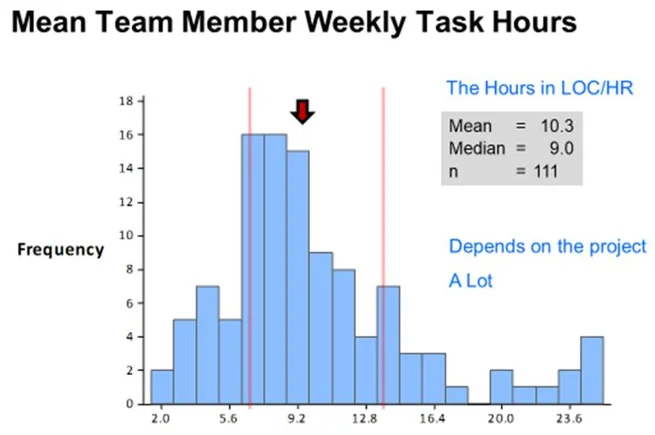

Figure 1: Mean Team-Member Weekly Task Hours

The productivity study I referred to in my earlier blog post used classroom conditions: data collected from our own work teaching the Personal Software Process (PSP). But our data from industrial practice shows that direct hours--finger-to-keyboard time--varies considerably. One study I conducted looked at the number of direct hours per week for the developers on 111 teams. I found that the average individual spent just 10.3 hours per week, as shown in Figure 1. Only a quarter could achieve more than 13 hours and a quarter were below 7 hours. For an average team, their weekly direct effort had a standard deviation of 25 percent. The variation among individuals was much larger. In other words, just finding time to work caused as much variation as the speed of work.

These data probably seem low, but they resemble folk notions such as the 2.5 loading factor that some early proponents of Agile methods used as a conversion between ideal hours and actual calendar time. Yet, they often found that 2.5 was too optimistic. Regardless, using this loading factor for a 40-hour week yields an estimate of 16 hours (40/2.5 = 16) per week. While this estimate may seem low, note that it is a higher number than what we saw in about 80 percent of the developers in our research. Ultimately, the load factor fell out of use in Agile, in part because it was only a subjective measure, open to criticism for sandbagging (being too low). Nonetheless, the data show that direct time is a constraint.

This study also suggests that to improve productivity, we should increase the available time. After all, just a few hours of direct time can be a large proportionate increase. Before managers teach teams anything else, they should teach them awareness and management of their time. Then managers must give programmers the time they need to develop software.

Where Does the Time Go?

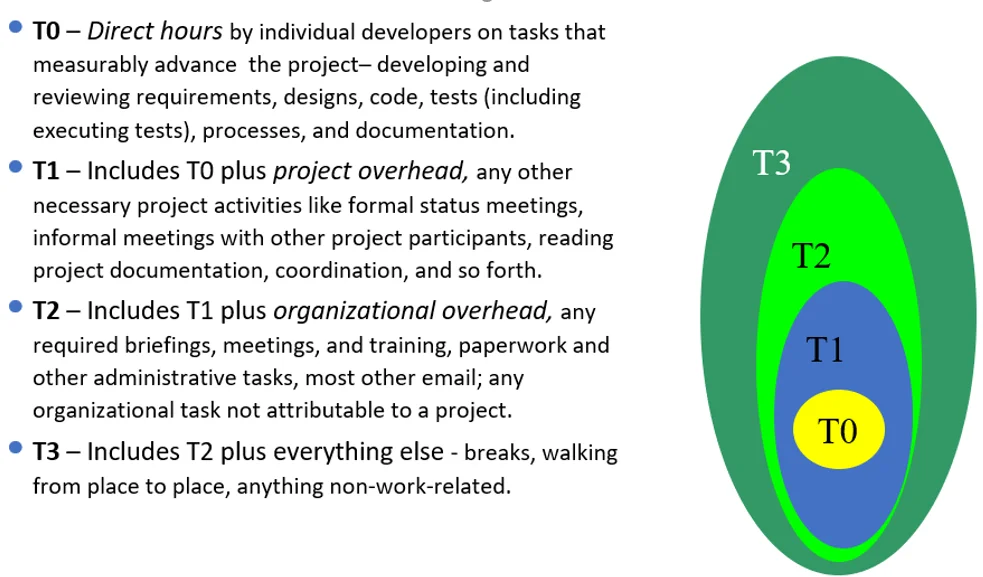

We spend much of our time at work on overhead that makes direct work possible. Some overhead is necessary. It includes training, answering email messages, attending and conducting status meetings, and walking from one place to another. To measure time, we categorized time in nested layers as we move farther from direct work. Figure 2 below depicts this nesting of time:

Figure 2: Nested-Time Accounting: Time Spent Is Nested in How Directly it Affects a Project

Some observations from Figure 2:

- T0 includes only time that can be attributed to a specific project work product and is what we measured in Figure 1. Although the average was 10 hours, it has a very wide range, most between 5 and 20 hours. Time available for T0 is what is left after the overhead from T1, T2, and T3.

- T1 includes the weekly project time that does not contribute to a single work product. The minimum time to be on a project is about 15% of a work week (6 hours), but this can easily go higher. When we measured T1, it was typically in the 17-23% range. Cost above the minimum is largely under direct management control.

- T2 was never measured directly, but can be estimated. The time commitments result from company or section policy over which neither staff nor first-line management have any discretion. T2 has a high variance from week to week.

- T3 is the normal face time at work and should be close to 40 hours. Without overtime, that is all the time available.

Having categorized the types of time and overhead, we can begin to think about what to do. As a project lead, I went after controlling T1 first, and I did this by limiting the use of staff with a "part-time" commitment. Since a project requires at least 6 hours of overhead, a full-time 16-hour developer split between projects becomes equivalent to two 5-hour half-time developers. Before we even consider the costs of task switching, using half-time developers therefore doubles T1 (project overhead) and cuts total available T0 (direct time) by a third. As a project leader, I literally traded away two half-time developers to convert another half-timer to full time. I won that trade after the calculation I just described showed me the opportunity. Another policy was to never accept a team member with less than a half-time commitment.

The math on part timers is stark. If project overhead is 6 hours, spreading a developer over three projects leave little time for anything but the project ceremonies. I allowed less than half time only for a critical skill outside, and then they were an external resource, not part of the team.

Productive Interventions

Management needs to enable developers to find more direct hours per week and make those hours productive. To begin, management must be attentive to the developers' needs to have quiet focused time to work. Open workspaces work against this. Open space may have other advantages, such as fostering collaboration and team interaction, but it is hard in open spaces for individual programmers to put in the focused time necessary for work that is intellectually demanding and creative. One common coping mechanism is for developers to put on headphones and tune everything else out; but of course, this defeats the collaboration intent of co-locating programmers in a common open space. To help knowledge workers concentrate, provide quiet workspace without distractions.

In our work with Team Software Process, we found that effective work periods generally range from about a half hour to a maximum of about three hours. Bursts of short work times led to excess startup overhead while longer work periods caused fatigue. This work time must be free from interruptions, email, meetings, or any other distractions. A two-to-three-hour "quiet work time" cannot happen without management support. When management guaranteed either daily three-hour windows or a couple of two-hour windows of uninterrupted time, weekly direct times generally exceeded 15 hours per week.

Another fruitful intervention involves the management of meetings. When you consider the number of person-hours consumed by meetings, it becomes clear that they are extraordinarily expensive. Here are some tips on how to run meetings efficiently, thereby freeing up more time for direct work:

- Don't invite people who don't need to be there.

- Keep the meeting short and on point, always use an agenda, and stick to it.

- Be sure that everyone comes prepared to share specific essential information.

- Use meeting facilitation and a timekeeper to avoid drift.

- Always defer topics that involve a sub-team to a separate meeting.

- Schedule meetings at times that don't disrupt work. These times vary depending on the organization and team, but we frequently used before/after quiet time, before/after lunch, beginning/end of the work day.

Other actions that have worked include co-locating teams, placing teams in a remote area away from distractions, moving meetings to natural break times, and simply asking the team for suggestions. Success was a combination of empowering the team members and management supporting the team when they needed management's help.

These guidelines may sound trivial, but people would rather work than attend meetings, and limiting time spent in meetings can be worth a 15-25% productivity boost. A couple of hours reclaimed from meetings per week adds two hours to the direct work. That's a 20% improvement to a baseline 10-hour week or 15% of a 15-hour week.

How Managers Should Not Respond to Schedule Pressure

Having reviewed positive interventions, I want to caution managers about some expedient ways to raise a team's direct hours that are not useful and that are often harmful. These naïve interventions have the same basic theme: to reward people for face time or for looking busy. These dubious ways to "reward and punish" are sometimes subtle. The following are a few examples:

- Be vocally and publicly proud of individuals or teams achieving high task hours or putting in extra time.

- Dictate goals for how many direct hours per week they should achieve.

- Press for increased "velocity."

- Ask about direct hours often, and ask how much higher the team or individuals can get them.

Such measures do sometimes have a short-term positive benefit and can get people to work longer hours, ignore non-task work, or ignore other assignments. While this can have positive results for an individual project, these sorts of measures are never sustainable and have negative consequences for the organization over time. Sustainable change is achieved not by setting arbitrary goals, but by changing underlying systems.

Most people outside a team won't understand how that team can be working long hours, often exceeding 40 hours per week, yet only putting 20 hours, 15 hours, or even fewer per week to tasks that directly move the project to completion. It is the manager's responsibility to protect the team members and manage expectations with other stakeholders.

Real Results

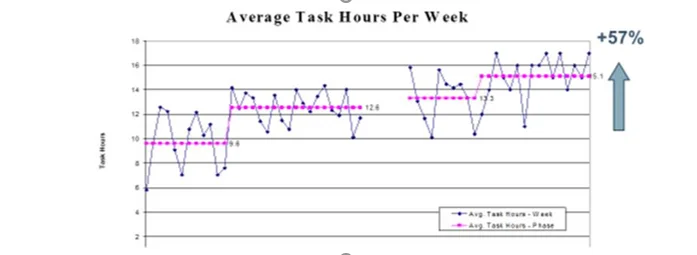

In one project our TSP team consulted on, we improved average task hours per developer per week from 9.6 hours to 15.1 hours by using these techniques (see Figure 3). Over the course of a year the project implemented quiet times, introduced facilitated meetings, and improved status reporting. The productivity gains shown in Figure 3 are a typical result. Without counting anything else, we routinely boosted productivity by more than 50% just with teaching the teams and managers the basics of time and being. A welcome side benefit was that developers became less stressed as more time became available to actually get the work done.

Figure 3: Improving Direct Hours Improves Productivity

Looking Ahead

In this post I have described the single most effective way that management can increase productivity with existing staff. Knowledge work requires focused time, but most don't manage this scarce resource effectively. We saw similar problems in every software project engagement I took part in, and these interventions always had an impact.

Getting control of productive time is only the first step. In a future post, I will describe force multipliers--proven techniques managers can use to improve the productivity during those productive direct hours.

Additional Resources

Programmers and managers interested in learning how to incrementally collect data and use that information to improve performance can review Team Software Process and Personal Software Process materials.

Read the first blog post in this series, Programmer Moneyball: Challenging the Myth of Individual Programmer Productivity.

Read other SEI blog posts by Bill Nichols.

More By The Author

Get updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedGet updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed