Cybersecurity Architecture, Part 2: System Boundary and Boundary Protection

PUBLISHED IN

Insider ThreatIn Cybersecurity Architecture, Part 1: Cyber Resilience and Critical Service, we talked about the importance of identifying and prioritizing critical or high-value services and the assets and data that support them. In this post, we'll introduce our approach for reviewing the security of the architecture of information systems that deliver or support these services. We'll also describe our review's first areas of focus: System Boundary and Boundary Protection.

Reviewing System Architectures

Information systems that perform or support critical business processes require additional or enhanced security controls. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800-53, Revision 4, security architecture includes, among other things, "an architectural description [and] the placement/allocation of security functionality (including security controls)." Security architecture can take on many forms depending on the context, to include enterprise or system architecture. For the purposes of this and subsequent blog posts, the term architecture refers to an individual information system, which may or may not be part of a larger enterprise system with its own architecture.

Incorporating a system architecture review into your security assessment can help stakeholders gain a comprehensive understanding of risk to the mission or business. How do you develop and implement a security architecture review process? What kinds of information should you collect and analyze?

Prioritize the Highest Value Systems for Review

No organization will have the resources to assess the architecture of every system. The organization should have a process for prioritizing systems and data according to their significance to the business or mission. One method is to identify the potential impact to the organization (such as Low, Moderate, or High) resulting from the loss of confidentiality, integrity, or availability (the "CIA Triad") of the information and information system.

Start the Review

A comprehensive security architecture review might explore everything from enterprise-level policy to role-based access control for a specific database. To achieve a holistic understanding of the system, the review team should include personnel with diverse backgrounds. When the CERT Division of the SEI performs security architecture reviews, our teams of three to four people often include system engineers, software developers, penetration testers, and security analysts.

Our security architecture reviews have three steps:

- Collect relevant information by reviewing the system's security and design documentation and conducting interviews with subject matter experts.

- Review and analyze the information, documenting findings or identifying additional information that needs to be collected.

- Summarize the findings and present recommendations in a written report.

Organizations can develop a formalized, documented process to suit their needs as their security architecture review capability matures.

Focus Areas

Our methodology for reviewing system architecture is a systematic, repeatable process that

- focuses on high-value services

- takes an outside-in approach, moving from the system boundary or perimeter to the system level

- often includes a review of enterprise-level systems and processes that affect the security of the system

- uses focus areas to drive analysis

This post will cover two focus areas: System Boundary and Boundary Protection. In future posts, we'll cover 11 other focus areas.

System Boundary

To properly identify an information system's boundary, you must identify not only where the data is stored, but also where system data flows, as well as critical dependencies.

Regulatory requirements can play a big role in properly defining a system boundary. NIST SP 800-37, Revision 1, has a flexible definition: "the set of information resources allocated to an information system." The Payment Card Industry (PCI) Data Security Standard (DSS) has a much more rigid definition: the systems that store, process, or transmit Card Holder Data (CHD) or sensitive authentication data, including but not limited to systems that provide security services, virtualization components, servers (web, application, database, DNS, etc.), and network components.

When analyzing the security architecture, it is critical to enumerate and document all of the applications and systems that store or process the system's data. In some cases, a large boundary can encompass the entire operating environment, including directory services, DNS, email, and other shared services. Whether such a boundary is too large can depend on the standard in use: NIST guidance might consider such services outside the boundary, while the PCI standard might include them. A boundary that is too large could inherit risk from systems that are outside the administrative and technical control of an information system owner--the individual or department with overall responsibility for the system.

A too-narrow boundary could exclude system resources from the level of protection required by the system owner. Boundaries are often too narrowly scoped and exclude critical dependencies--systems that could have a direct impact on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the high-value system being reviewed. If there are critical dependencies outside the boundary and they could affect the CIA of the system, you must account for the additional risk.

With a defined system boundary, the organization should have a well-defined and documented diagram depicting of all of the entities that store or process system data.

Boundary Protection

Using our outside-in approach, the next step is to review the system's boundary protection. Boundary protection is the "monitoring and control of communications at the external boundary of an information system to prevent and detect malicious and other unauthorized communication." Protection is achieved through the use of gateways, routers, firewalls, guards, and encrypted tunnels.

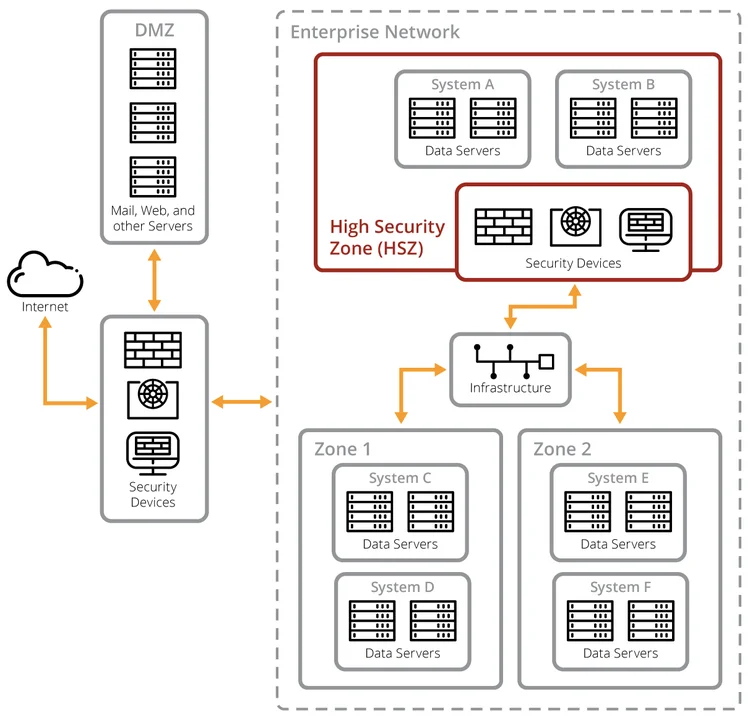

Figure 1 presents a notional enterprise architecture with two high-value systems residing in a high security zone (HSZ). The HSZ security devices provide boundary protection for the high-value systems in addition to protections provided at the enterprise level, such as the security devices between the enterprise network and the internet and DMZ.

Figure 1. Notional Enterprise Architecture

The CIA requirements for the other systems that reside in the hosting environment, might be very different from the CIA requirements for the high-value system. Regardless, we recommend employing boundary protection specific to the high-value system to ensure that it is sufficiently isolated, including from the rest of the enterprise. In addition, all of the traffic entering and exiting the high-value system environment should be inspected.

Required inbound and outbound traffic for high-value systems should be understood and documented at the IP address, port, and protocol level of detail. This information can be used to ensure that system network communications are denied by default and allowed by exception, in accordance with the security design principle of Least Privilege.

Some boundary protection capabilities might be provided by the enterprise or the environment that hosts the high-value system. For these inherited controls, it is important to understand the implementation details for each control and the protection that the control provides. Do these controls, and the manner in which they are implemented, meet your control objectives, or "statement[s] of the desired result or purpose to be achieved by implementing [a] control"?

Your organization's protection strategy should carefully orchestrate and thoroughly document the interplay among the enterprise, hosting environment, and high-value system boundary protection capabilities. This protection strategy is typically described in the high-value system's System Security Plan, or SSP.

Here are some questions that can help guide your boundary protection analysis.

- What boundary protections are required or recommended for a high-value system with these CIA requirements? (For example, traffic to and from the high-value system is restricted to only traffic that is required for the operation of the system.)

- What boundary protection capabilities are provided by the enterprise or the hosting environment?

- What boundary protection capabilities apply to the high-value system?

- Considering all of these capabilities, are my boundary protection objectives met?

Next Time

In this post, we presented an outside-in approach to security architecture reviews that has worked for us, starting with two focus areas, System Boundary and Boundary Protection. In Part 3 of our Cybersecurity Architecture series, we'll discuss three more focus areas: Asset Management, Network Segmentation, and Configuration Management.

More By The Authors

More In Insider Threat

PUBLISHED IN

Insider ThreatGet updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedMore In Insider Threat

Get updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed