Introducing the Minimum Viable Capability Strategy

It's common for large-scale cyber-physical systems (CPS) projects to burn huge amounts of time and money with little to show for it. As the minimum viable product (MVP) strategy of fast and focused stands in sharp contrast to the inflexible and ponderous product planning that has contributed to those fiascos, MVP has been touted as a useful corrective. The MVP strategy has become fixed in the constellation of Agile jargon and practices. However, trying to work out how to scale MVP for large and critical CPS, I found more gaps than fit. This is the first of three blog posts highlighting an alternative strategy that I created, the Minimum Viable Capability (MVC), which scales the essential logic of MVP for CPS. MVC adapts the intent of the MVP strategy--to focus on rapidly developing and validating only essential features--to systems that are too large, too complex, or too critical for MVP.

The second post, One Size Doesn't Fit All: Release Scope Versus Frequency, makes a case for defining an MVC roadmap that includes small-, medium-, and large-scope releases. The third post, How to Deliver a Minimum Viable Capability Roadmap, shows how, just as for MVP, the MVC strategy requires well-formed architecture and early validation.

Together, these three posts define the MVC strategy.

What is a Minimum Viable Product?

Although the Minimum Viable Product Strategy can be effective for early-stage development of certain kinds of applications, it isn't as useful for systems where unpredictable field experiments have unacceptable risks and doesn't address release-planning issues common to large and long-lived CPS. The MVP strategy works well in its niche, but as many have noted, When a map and the terrain differ, believe the terrain.

The MVP strategy focuses software development on the smallest feature set of value to a user or customer. Because this usually begins with a guess, MVP developers are encouraged to fail fast, quickly releasing a series of MVPs to learn which features are more or less valuable or undesirable. This often sparks insights and even a pivot to a fundamentally different product. The cycle is repeated until the product feature set is sufficiently grown and validated.

Paul Keck defines minimum as "...the least amount of features that will satisfy your target customer's top need(s)." According to Keck, viable means that it "...implements or enables a business model to collect money and turn a profit for a sustainable business." Finally, Keck writes that it is a product if it "can satisfy the minimum need for a specific someone in a way that makes a profit."

Many view MVP as a key part of Agile release planning: it brings in the voice of the customer early, can reduce wasted work, and helps a team stay focused.

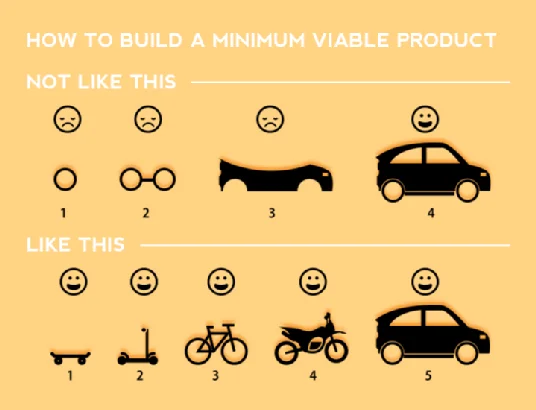

The figure below is often used to illustrate the MVP strategy. (This cartoon has become an Internet meme-there are many variations and no clear author.) It depicts two ways to build a vehicle: The first is compositional-subsystems are built in succession and then assembled. Delivery of value to the customer (mobility) occurs only after final assembly. The producer must carry all risks until the market renders a judgment on the final assembly.

The second approach is evolutionary--the simplest possible mobility solution is produced first so that customers get the value of mobility first, even if limited. The producer gets market feedback before making expensive design commitments. Eventually, a full-featured vehicle is delivered.

The process of discovering an MVP is what Alberto Savoia calls pretotyping--"Building the right it before you build it right." MVP guides early-stage innovators, startups in particular, to focus their limited resources to minimize the risk of producing a dud that won't sell. While this may seem like simple common sense, it deals with two problems that often lead to duds: (1) the tendency of startup founders to assume that the vision they love will have universal appeal and (2) the tendency of developers to lavish effort on technology for its own sake. Without a rapidly enforced reality check, these tendencies can easily result in an over-engineered white elephant.

Software startups developing mobile apps and web services for social media were the original context of the MVP strategy. Pushing out updates frequently--often representing the work of just a few short sprints--proved to be a useful corrective to wrong guesses and over-engineering.

The success of MVP isn't just a result of rapid iteration and intense focus. It has relied on the proliferation of cloud-hosted software as a service (SaaS) with APIs for everything. Application development is now more service integration than greenfield programming using feature-rich open source tool chains. When this nearly free ecosystem can support an MVP, development time is easily reduced by a factor of 10 compared with hand-crafting services.

Minimum Viable Capability

Although the cartoon above conveys the essential MVP notion, I had to suspend too much disbelief to map it to CPS development. It uses a lot of artistic license to present several complex abstractions and doesn't even attempt to provide a visual metaphor of incremental software functionality. The illustrator suggests that the cost, scale, and work of building skateboards, scooters, bicycles, and cars is roughly the same. While several bicycle companies have gone on to make motorcycles, nearly all stuck to bicycles and none became automobile manufacturers.

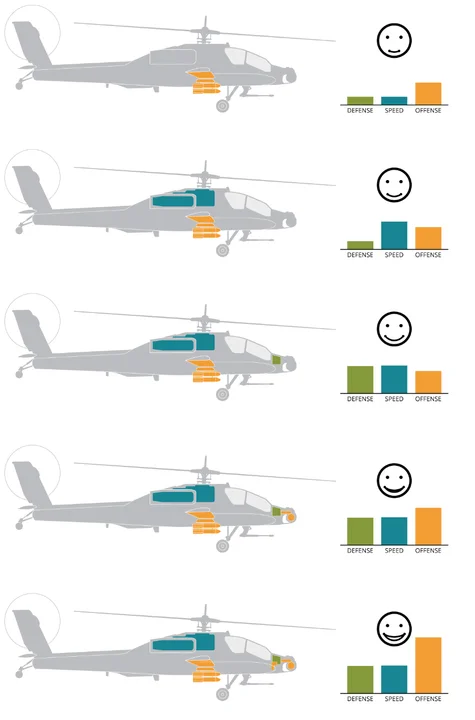

However, I couldn't sketch any equally intuitive alternative, so I asked SEI graphic artist Kurt Hess to develop something would make more sense for CPS developers. Kurt produced the graphic below.

Capabilities are often related to modes of operation and achieved by cooperation of multiple components and layers. Three notional capabilities are shown: defense, speed, and offense. For each, the customer defines the following:

- a threshold (the bare minimum acceptable performance)

- a target (the desirable performance level)

- stretch (high performance that would be useful, but is not necessary.)

The bar charts at right suggest the extent to which each release achieves these goals. Overall value to the operator is suggested with wider smiles.

So, we had our MVP graphic for a CPS. But then product no longer seemed apt. The graphic reflects the CPS reality that releases are composed of multiple capability levels, not as a unitary product. Dropping the P for product from MVP, the capability-oriented strategy was then MVC, with C for capability.

How is MVC different from MVP?

MVC differs from MVP in each of its essential elements.

Focus: A product is a unitary whole, where a capability is one aspect of a product. This capability-oriented view is part of the reason that MVC scales to large systems.

Minimality. The MVP approach is simply a special case of charting a product roadmap--a plan that allocates feature sets to future releases. Like an MVP, MVC releases should achieve minimal and feasible support for a capability or capability set. Unlike an MVP, MVC recognizes that the work for an initial version is often extensive--the hill to climb to that first version can be long and steep. There are often core capabilities that must be delivered as a whole to achieve minimally acceptable safety, security, and performance. For example, you cannot fly anything less than an airworthy aircraft--that platform is an MVP, not its constituent capabilities. A first sign of big-system trouble, however, is often piling on scope, time, and cost without regard for necessity or schedule effects. MVC releases of any scope still should be minimal-as small as possible but no smaller.

Rapid Validation. The MVP strategy relies on rapid customer feedback to shape a product quickly. But instead of stars in an app store, CPS capabilities must be evaluated by testable measurements of effectiveness. An essential part of the MVC strategy is to establish early testing and validation that provides actionable feedback in time to make a difference.

Architecture. MVPs are often built on a SaaS and open-source development ecosystem that is inexpensive, well-understood, and stable. In contrast, CPS development is often capital-intensive and dependent on other digital, electrical, and mechanical systems, so it has an uneasy truce with open source. Where MVP takes a stable enabling architecture for granted, MVC recognizes that it must be built along with capabilities.

Next Up: Setting Scope and Frequency

CPS sponsors, producers, developers, and testers grapple with ever-increasing demands for advanced functionality, interoperation, security, and reliability. They are also now encouraged to be Agile about it.

While the minimalist spirit of the MVP strategy is a good thing, it doesn't address CPS systems engineering and product planning issues. The MVC strategy takes account of interdependencies to deliver capability the earliest possible time, but no sooner.

The second post of this series will explain how release scope (e.g., "minimal") is related to release frequency and why an MVC roadmap should include small, medium, and large releases.

Get updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedGet updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed