Cybersecurity Capacity Building with Human Capital in Sub-Saharan Africa

In 2020, the United Nations estimated the total population of Africa at 1.3 billion, with 60 percent of the population under the age of 24. At the same time, the population continues to embrace, in ever-increasing numbers, the use of the Internet and other web technologies. With this growth in countries that often lack the necessary infrastructure and expertise comes the inevitable increase in cybersecurity incidents and data breaches. As government leaders work to create a stable and extensive technology infrastructure, they must also work to provide opportunities for significant training and skills acquisition for current and future African government employees, professionals, and students. The mere existence of fast Internet and foreign investments is not sufficient. Instead the focus is on the creation of skilled cybersecurity human capital that will work with existing technologies and develop new innovation to solve real-life threats unique to the African continent. This blog post, which is adapted and excerpted from a recently published paper that I coauthored with Michelle Ramin, explores issues surrounding cybersecurity capacity building with human capital in Africa.

What Is Capacity Building of Human Capital?

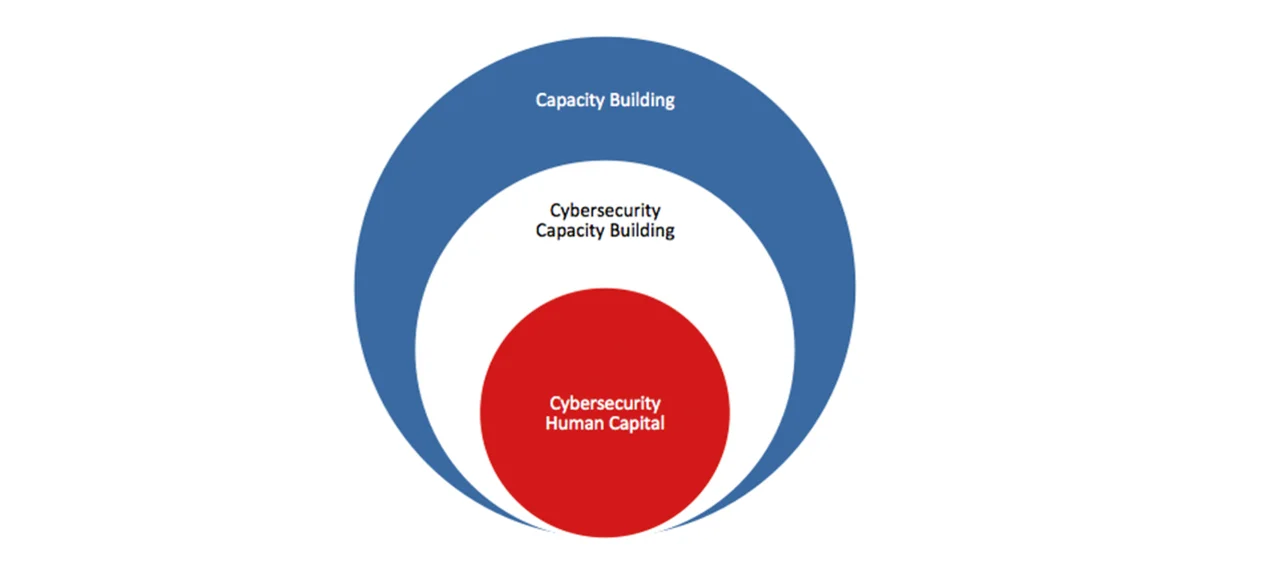

Capacity building of human capital is defined as the strategic development of educating, training, and mentoring of cybersecurity personnel. It is a continual learning process in which cybersecurity personnel conduct exercises in real-life scenarios and engage in knowledge transfer, proficiency improvement, capability development, and skills building across levels of complexity.

This definition emphasizes the role of stakeholders, including government, private sector, academic institutions, schools, and individuals. Capacity building of human capital is thus a critical component of cybersecurity capacity building. “Human capital” refers to the human resources, their understanding, knowledge, skills, and capabilities to perform. Figure 1 depicts the connection among the various components noted above.

Cybersecurity Capacity Building in Africa and U.S. Government Partnership

Efforts on behalf of the United States to extend capacity building in Africa have been ongoing. Many African countries lack financial resources, Internet infrastructure, and homegrown cybersecurity expertise. In 2014, 54 African countries making up the African Union (AU) adopted the Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection (also known as the Malabo Convention) with the aim of securing electronic transactions, protecting personal data, and deterring cybersecurity and cybercrime.

As time progressed, only a handful of countries endorsed the Malabo Convention and adopted a formal policy, resulting in a weak alliance and implementation. Many countries appeared to be working independently and thus were sluggish to adopt and adhere to a regional cybersecurity strategy. In fact, under the guidance of the U.S. Department of State’s Office of the Coordinator for Cyber Issues, in Africa eight countries have created national cybersecurity strategies, and 13 countries have organized national computer emergency response teams.

Such a cybersecurity digital divide has a far-reaching effect on the region’s economic productivity, as well as the ability of state governments and local business organizations to hire local cybersecurity human capital. The AU has long advocated for the collaboration and sharing of stable technology and Internet infrastructures among members because of the high cost of investment. Adopting such an approach, however, requires establishing trust among AU members as part of long-term collaborative efforts.

In the United States, several consortia enable resource sharing. For example, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Cybersecurity Information Sharing and Collaboration Program (CISCP) enables the exchange of unclassified actionable, relevant, and timely information among stakeholders through trusted public and private partnerships across critical infrastructure (CI) sectors. The CISCP program helps stakeholders manage cyber risks through analyst-to-analyst sharing of applied threat and vulnerability information, such as indicator bulletins, analysis reports, joint-analysis reports, malware-findings reports, malware-analysis reports, and joint-indicator bulletins. This information shared among CISCP stakeholders is governed using the Traffic Light Protocol (TLP), allowing the submitter to control the handling, classification, and sharing/dissemination of their information.

Another US-based cyber information sharing model is the Information Sharing and Analysis Center (ISAC) model. The ISAC is based on a hub-and-spoke architecture, where the central hub receives information from participating members (the spokes). In this architecture the hub can either redistribute the information received to its members or provide value-added services, augmenting the data in an effort to make it more useful and relevant to members.

To implement information-sharing mechanisms, many African nations are following these U.S. standards. Moreover, the State Department is stepping up its efforts to motivate and promote a holistic government-to-government approach to extend the cybersecurity capacity building in the region. As noted earlier, the cyber skills gap is also applicable to current employees. More often than not, the question that a security analyst will have is, “Now that I have these tools, what do I do with them?”

Enhancing cybersecurity capacity building enhances the ability of national governments to create CSIRTs to understand and respond to real-time cyber threats through information sharing, incident response coordination, and mitigation collaboration. The Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency defines a CSIRT as

a concrete organizational entity (i.e., one or more staff) that is assigned the responsibility for coordinating and supporting the response to a computer security event or incident. CSIRTs can be created for nation states or economies, governments, commercial organizations, educational institutions, and even non-profit entities. The goal of a CSIRT is to minimize and control the damage resulting from incidents, provide effective guidance for response and recovery activities, and work to prevent future incidents from happening

As I wrote in my 2017 post, national CSIRTs have taken a prominent role as points of contact in the coordination and response to national, regional, and international computer-security incidents. Previous and current administrations have set forth cybersecurity policies that enable the United States to pursue international cooperation in maintaining a globally secure and resilient Internet with partner and ally nations. In 2014 the SEI CERT Division and the U.S. Department of State Office of the Coordinator for Cyber Issues (S/CCI), in coordination with the Department of Homeland Security Office of International Affairs, began developing and implementing global cybersecurity capacity-building activities that support capability and capacity building for national-level CSIRTs.

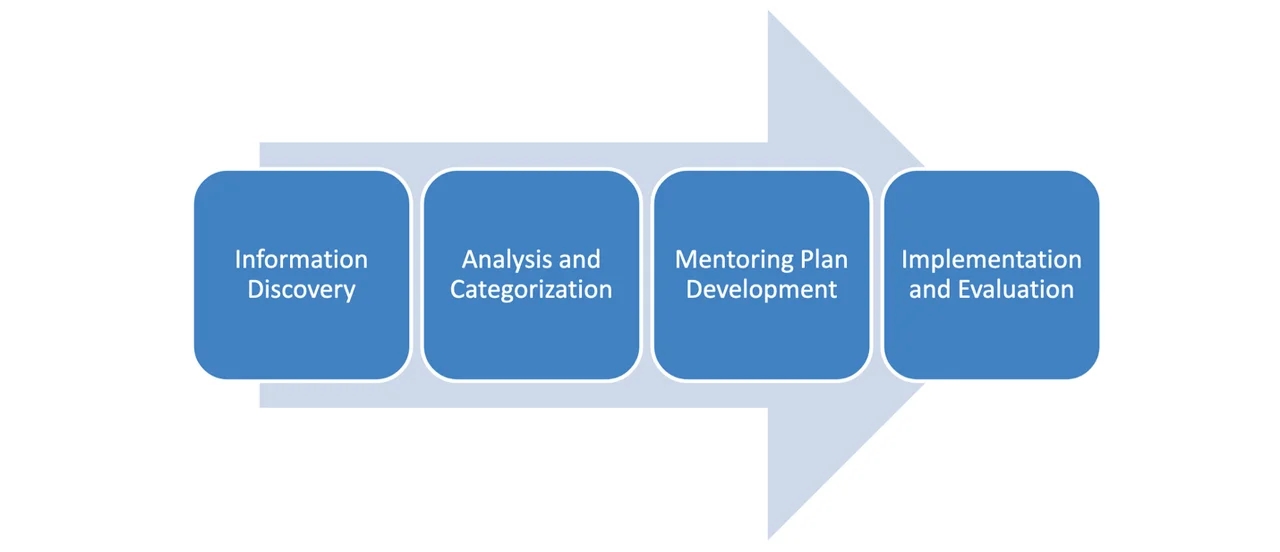

To determine the capacity in which a CSIRT operates, the SEI has developed the CSIRT Development Capacity Continuum. The continuum illustrates a CSIRT’s capabilities on a scale from 0 (a nascent CSIRT) to 5 (where the CSIRT is described as being on the “leading edge and innovative”). To classify a CSIRT within this continuum, a series of interviews are conducted with the national CSIRTs of the partnering nations. These interviews are within the scope of the SEI National CSIRT Development Mentoring Framework, which is applied in four linear phases, as shown in Figure 2 and described below.

Phase 1: Information Discovery. This phase helps the mentor team understand the organization requiring mentoring and determine the feasibility for providing assistance. The information gathered here is the foundation for all the other components on which the framework is built. The main activities in this phase include the following:

- Identify the assistance that the CSIRT desires.

- Submit an information-gathering survey to the CSIRT for completion.

- Perform a public-source literature review.

- Obtain insight about the CSIRT from post (the U.S. embassy in the country).

- Obtain insight from partner CSIRTs.

- Interview CSIRT members and constituents.

- Conduct an onsite visit with the CSIRT.

- Obtain insights from government or industry stakeholders in the country.

- Identify previous training or mentoring received by the CSIRT.

- Perform a national CSIRT assessment as part of the onsite visit (optional).

Phase 2: Analysis and Categorization. In this phase, data collected during the Information Discovery phase is analyzed and used to determine the current capacity of the mentee CSIRT, and a plan of action is recommended to help improve the CSIRT’s capability, including the following activities:

- Identify the CSIRT’s mission, goals, and scope.

- Identify current CSIRT activities, services, and operations.

- Identify CSIRT needs based on the assistance desired.

- Identify special circumstances.

- Benchmark the CSIRT against the CSIRT Capacity Development Continuum.

- Identify the CSIRT’s capacity level.

- Perform a gap analysis.

- Identify mentoring requirements.

- Identify potential mentors or partners.

Phase 3: Mentoring Plan Development. During this phase, activities jointly agreed on by the mentor and mentee are developed and documented. This process includes possible mentoring options, mentoring strategies and activities based on requirements, and the creation of a corresponding roadmap, plan of action, and milestones. It also includes socializing the plan with the mentee and its stakeholders. The main activities in this phase include the following:

- Identify relevant mentoring/assistance options.

- Choose mentoring strategies and activities.

- Create the mentoring plan and roadmap.

- Socialize and obtain agreement on the mentoring plan.

- Create a mentoring project plan and milestones.

Phase 4: Implementation and Evaluation. The final phase involves implementing specific mentoring tasks outlined in the mentoring and training plan, tracking the progress of the plan, and evaluating the success of the executed plan using an assessment methodology. Once the mentoring engagement is complete, the mentoring team may work with the framework maintainer to determine appropriate next steps based on what has been learned.

The main activities in this phase include the following:

- Implement the mentoring and training plan and roadmap.

- Track milestones and accomplishments.

- Gather feedback.

- Adjust plans as needed.

- Perform a postmortem.

- Assess success.

- Gather lessons learned for inclusion in the mentoring framework.

- Document the process as part of the organizational knowledge.

Establishing Cybersecurity Human Capital

As we stated earlier in the post U.S. State Department has worked with several African nations to establish cybersecurity human-capital capacity building. Moreover, a collaborative effort is ongoing as the participating countries continue to work on developing advanced stages of cybersecurity human-capital skills building.

The remainder of this post explores the importance of capacity building of human capital, which is a critical component of cybersecurity capacity building, as discussed above. The establishment of cybersecurity human capital involves several steps, beginning with the development and implementation of cybersecurity awareness programs.

A government agency will perform awareness campaigns, including slogans, posters, pamphlets, etc., collaboratively with stakeholders in the community (e.g., students, business organizations, government agencies). Other awareness activities include the creation of an annual Cybersecurity Month and the establishment of a web presence and social media campaigns. Moreover, awareness campaigns should be created for business leaders and executives in key industries, such as banking, retail, education, and healthcare, to educate them about the risks and threats in their organizations.

One example of a successful campaign developed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security is the creation of the slogan STOP.THINK.CONNECT. This slogan highlights to end users the risks that come with being online. This successful campaign has been extended internationally.

The second step in establishing cybersecurity human capital involves the development of education programs in primary, secondary, and post-secondary schools. As technology evolves, so does the cybersecurity landscape. To remain relevant, education programs should follow the lead provided by industry and keep up with changing technologies.

In a 2016 report titled The Evolution of Security Skills by IT certification authority CompTIA, 350 organizations were surveyed about the skill sets that were considered important on security teams. The top two skills identified were network/infrastructure security and knowledge of various threats, as shown in the graphic below. Both of these skill sets require that individuals not only gain an understanding of core concepts, but also remain current on the changing cyber landscape. Awareness campaigns involving C-level management and staff can be used to educate and inspire leaders to change policy and directives regarding security.

In Africa, Ghana has made a concerted effort to make cybersecurity a recognized household term. Since 2017, Ghana has conducted an annual awareness campaign during October in support of Cybersecurity Month, providing workshops for both the public and private sectors. Cybersecurity Month peaks with the Cybersecurity Week event, where Ghana unveils new cybersecurity services that the government will provide to all its constituents. The 2020 theme, “Cybersecurity in the Era of COVID-19,” provided events in all regions of Ghana, as well as several workshops and activities ranging from child online protection, panel discussions, and cybercrime and electronic-evidence workshops.

While such events are important for overall awareness and readiness, organizations wishing to develop cybersecurity programs must first identify existing assets and infrastructure and develop a clear understanding of the direction in which the business and its supporting technologies are headed. Research has shown that understanding these key components will help organizations determine the skills necessary for new team members and the skill sets that must be enhanced in existing team members.

The Future Course in Cybersecurity Human Capital Building in Africa

Challenges in developing human capacity and ultimately human capital are not unique to Africa. These are human challenges that apply to the global population. It is clear that understanding the development of human capital to meet current and future needs in the cybersecurity space is necessary for continual online safety of individuals and organizations, and for national security. Organizations must turn their attention to the cyber skills and literacy of their workforce with a focus on specific roles within teams and team functions within organizations.

Our future research will focus on the intersection of both regional and organizational culture and its impact on cybersecurity human-capital building. While human capital represents the knowledge, skill sets, and intangible assets that add economic value to individuals, it is something that cannot be statically measured as demonstrated by Enrico Calandro and Patryk Pawlak in Capacity Building as a Means to Counter Cyber Poverty. What can be measured is the value that individuals bring in the form of return on investment (ROI).

Additional Resources

This post is adapted and excerpted from the following paper by Michelle Ramin and Angel Hueca (2021). Cybersecurity capacity building of human capital: Nations supporting nations. The Online Journal of Applied Knowledge Management (OJAKM), 9(2), 65-85. https://doi.org/10.36965/OJAKM.2021.9(2)65-85

Read the SEI technical report Best Practices for National Cyber Security: Building a National Computer Security Incident Management Capability, Version 2.0.

Read the SEI whitepaper CSIRT Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ).

Read the FIRST CSIRT Framework.

Read the report Combatting Cyber Threats: CSIRTs and Fostering International Cooperation on Cybersecurity from the Global Commission on Internet Governance.

More By The Author

Get updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedGet updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed