Toward Efficient and Effective Software Sustainment

Our SEI blog has included thoughtful discussions about sustaining software, such as the two-part post "The Growing Importance of Sustaining Software for the DoD." Software sustainment is growing in importance as the lifetimes of hardware systems greatly exceed the normal lifetime of software systems they are partnered with, as well as when system functionality increasingly depends on software elements. This blog post--the first in a multi-part series--provides specific examples of the importance of software sustainment in the Department of Defense (DoD), where software upgrade cycles need to refresh capabilities every 18 to 24 months on weapon systems that have been out of production for many years, but are expected to maintain defense capability for decades.

Across the history of the U.S. military and its industrial support, we often see an ebb and flow of attention to the industrial base. At times, the focus is on modernization; and at others, the focus is on sustainment. Both are essential, and some of the greatest challenges are in managing at the interfaces between the contractors in the industrial base and the sustainment elements, which are often considered organic capabilities that need to reside with the government.

The DoD has various names for its organic sustainment organizations. In some cases, these organizations only fix existing equipment after damage or use in an arduous environment, such as Afghanistan. But virtually every military system is also planned for periodic visits to a site where both repair and some modernization of subsystems occur. In the Air Force, for example, Air Logistics Centers (known as "depots") are responsible for keeping the majority of the Air Force's weapon systems modernized over their lifetime after being created by the industrial base of contractors. Sustainment responsibility may remain with the original contractor, though this blog post focuses on challenges faced when responsibility transitions from the originating contractor to the government organic sustainment organizations.

Overlaying this sense of sustainment is software that requires regular attention. For hardware, a part can wear out and must be replaced. The replacement is typically identical to the one being removed, so that form, fit, and function are not an issue. Software doesn't break like hardware sometimes does--but it is often the case that users will find system behaviors that must be changed to provide the capabilities desired in constantly evolving work environments. Often software update cycles overlay the system refurbishment cycle to keep the systems functioning as effectively as possible. Sometimes the software fixes are small patches to the existing collection of programs. In other cases, they are major elements of new functionality, often in response to new sensors or weapons, or to address an expanded threat spectrum.

Sustainment Versus Development

The business rhythms of sustainment and development are often different. For example, a sustainment organization can often package many small fixes into a single upgrade without having to devote significant time to reconsidering the architecture at the front end of the cycle, or to do extensive system testing after creating the patches. As the amount of software grows for full modernization efforts, the importance of the full engineering life cycle grows with it. Without a rigorous approach to the engineering V-model, the risks of failure grow exponentially.

Recent studies of U.S. Air Force aircraft sustainment needs by the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board and the National Research Council characterized sustainment as modifying/correcting existing code and/or developing new functions or performance improvements that enhance weapon system relevance or capability. A key insight from these studies is that software development and sustainment have nearly identical processes when developing new functions or performance improvements. This similarity reflects the need mentioned above for full consideration of the architecture and interfaces once changes exceed that of "bug fixes."

Since many of our weapon system platforms are expected to live for decades--rather than through a single conflict--the software sustainment strategies demand first-class software development capabilities across a lifecycle that is much longer than what is typically seen in the commercial environment. The venerable B-52 bomber, for example, is now being positioned for an update so it will remain an integral part of the Air Force's strategic bomber force through 2040--a lifetime of about 90 years. Put another way, pilots who will one day fly B-52s may not even be born yet!

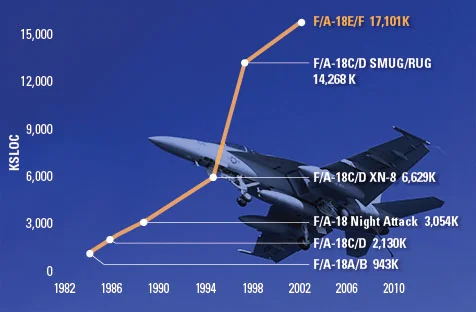

The graphic below shows the expanded capabilities from software upgrades across the Navy's F/A-18 product line. The large increases in lines of code (thousand of source/software lines of code, or KSLOC) are associated with major increases in capability to attack at night and, later, to handle a rapid growth in smart weapons that must be fed guidance and other updates in-flight. Although this increase in capability was delivered while the F-18 remains in production--and therefore is supported by a robust contractor capability--a sustainment plan is needed so that these capabilities can also be provided when F-18s are no longer in production.

(Source: Office of the Secretary of Defense)

The second blog post in this series will describe the Navy approach for the F-18 in more detail. The key insight at this point, however, is that all of our systems will continue to grow their capabilities well after production ceases. An effective sustainment strategy therefore needs to include robust software capability after major systems contractors have moved on to the next generation of hardware.

Toward Efficient and Effective Software Sustainment

What may not be well known are the steps being taken by many in the organic government community of software developers to raise their capabilities through a clear focus on software quality. In some cases, this progress has been measured against the CMMI model for development. In other cases, the Team Software Process has been used either within a CMMI effort or in addition to any CMMI-based process improvement. These techniques are being complemented with modern technologies (such as development tool suites) and increased attention to architectural strategies (such as software product lines). Successes have been seen across the Army, Navy, and Air Force, where sustainment organizations have displayed deep software expertise on weapons systems in their domain of responsibility. This capability is noteworthy as we see more emphasis on affordability and better buying power. The key to keeping our weapon systems modernized during a period of austerity is to rely on organizations that have demonstrated their own ability to modernize their internal capabilities.

While these achievements have been noteworthy, more progress is needed to keep pace with the growing demands on software sustainment organizations as DoD new-start programs are being reduced in favor of prolonging legacy systems. The SEI recently participated in a National Research Council study on sustainment in the Air Force. A key recommendation for software sustainment documents a key challenge:

- "Recommendation 4-5. The Air Force should focus the same, arguably more, attention and investment as that given to equipment in the actual weapon system on the tools used for software maintenance. Maintaining currency between test laboratories and actual weapon systems is fundamental for dealing with timing, details of hardware interface behavior, and concurrency."

Given the importance of software to sustaining DoD weapons systems, it is essential that the DoD adopt an enterprise approach to software sustainment throughout the lifecycle of their weapons systems. This enterprise approach should ensure that program acquisition and sustainment strategies reflect and protect the DoD's strategic investment in software by enacting robust software engineering processes/practices throughout the organic and contractor workforces. Achieving this enterprise approach requires greater recognition that effective software sustainment requires DoD investments and commitments throughout weapon system lifecycles, including early phases where advanced software R&D plays an important role to identify and retire technical risks that will occur during sustainment. Likewise, the DoD needs to facilitate and incentivize collaboration activities between contractors and organic sustainment organizations to ensure seamless transition of responsibilities and workload for long-lived programs.

Concluding Thoughts

This blog post surveys some of the broad ground of software sustainment for the DoD. Subsequent posts will provide concrete examples from DoD sustainment organizations. The F-18 sustainment activities mentioned above will be described further in the next post. Although these upcoming posts focus on government programs, the McKinsey Quarterly has recently published a companion for industry, which makes it clear that the challenges of software sustainment extend to other domains beyond defense and aerospace.

Additional Resources

To read the Crosstalk article "Extending the TSP to Systems Engineering: Early Results from Team Process Integration", please visit

www.crosstalkonline.org/storage/issue-archives/2010/201007/201007-Carleton.pdf

Recent studies of U.S. Air Force aircraft sustainment needs by the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board and the National Research Council characterized sustainment as modifying/correcting existing code and/or developing new functions or performance improvements that enhance weapon system relevance or capability.

Get updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedGet updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed