Three Pilots of the CERT Software Assurance Framework

Software is a growing component of business and mission-critical systems. As organizations become more dependent on software, security-related risks to their organizational missions also increase. We recently published a technical note that introduces the prototype Software Assurance Framework (SAF), a collection of cybersecurity practices that programs can apply across the acquisition lifecycle and supply chain. We envision program managers using this framework to assess an acquisition program's current cybersecurity practices and chart a course for improvement, ultimately reducing the cybersecurity risk of deployed software-reliant systems. This blog post, which is excerpted from the report, presents three pilot applications of SAF.

Field experiences of SEI technical staff indicate that few programs currently implement effective cybersecurity practices early in the acquisition lifecycle. In particular, traditional security engineering approaches rely on addressing security risks during the operation and maintenance of software-reliant systems. The costs required to control security risks rise significantly, however, when organizations wait until systems are deployed to address them. Recent Department of Defense (DoD) directives (see here and here) have begun to shift programs' priorities regarding cybersecurity. As a result, researchers from the CERT Division of the SEI have started SAF to catalog the cybersecurity practices needed to acquire, engineer, and field software-reliant systems that are acceptably secure.

The overarching goals of the SAF are to (1) establish confidence in the program's ability to acquire software-reliant systems that are secure and (2) reduce the cybersecurity risk of software-reliant systems. When developing and piloting SAF, we leveraged the software acquisition and cybersecurity expertise of a number of SEI staff members and referenced a variety of acquisition, development, process improvement, and cybersecurity documents, including

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 800-53, titled Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations

- NIST Special Publication 800-37, titled Guide for Applying the Risk Management Framework to Federal Information Systems: A Security Life Cycle Approach

- Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI) 5000-2, titled Operation of the Defense Acquisition System

- Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI)

- Build Security In Maturity Model (BSIMM)

The remainder of this post details how we recently used the SAF to support the following three pilot engagements:

- conducting a gap analysis of the software assurance services provided by an organization

- integrating software security practices into an organization's existing policies and procedures

- generating a candidate set of cybersecurity engineering metrics

Our technical note features the structure and content of the SAF. In this blog post, we decided to focus on how we are using the SAF to support our field work. These pilots demonstrate the applicability of the framework for assessing, improving, and monitoring a program's cybersecurity engineering practices.

Gap Analysis

We initially developed the SAF while conducting a gap analysis at the request of a customer. The goal of the analysis was to identify gaps in current and planned software assurance services offered by a DoD service provider. We developed SAF v0.1 (our prototype version) after our search of the applicable literature failed to find a satisfactory framework to serve as the basis for the gap analysis. Version 0.1 used the Defense Acquisition Management Framework (defined in the DoD's Operation of the Defense Acquisition System) as its main organizing structure.

The following list summarizes each of the areas depicted in the figure above:

1. Governance Infrastructure--foundational practices needed to establish and implement a program's assurance policies

2. Materiel Solution Analysis (MSA)--the assurance activities that must be performed during the MSA phase of the acquisition lifecycle

3. Technology Development (TD)--the assurance activities that must be performed during the TD phase of the acquisition lifecycle

4. Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD)--the assurance activities that must be performed during the EMD phase of the acquisition lifecycle

5. Production and Deployment (PD)--the assurance activities that must be performed during the PD phase of the acquisition lifecycle

6. Operations and Support (O&S)--the assurance activities that must be performed during the O&S phase of the acquisition lifecycle

7. Secure Software Development--the technical activities that must be performed when developing software with desired security characteristics

8. Secure Software Operation--the technical activities that must be performed when operating software in a secure manner

9. Software Security Infrastructure--foundational practices needed to develop and operate secure software

The first step in a gap analysis activity is to collect relevant data. We conducted interviews with personnel from the service provider to gather information about software assurance services currently offered by the organization. We then mapped the software assurance services provided by the organization to the appropriate practices in the SAF v0.1. After completing the mapping, we identified gaps where the current services did not adequately address the practices to which they were mapped. We also identified high-priority services that the provider might consider offering in the future.

As noted above, the practices of the SAF v0.1 were organized using the structure of the Defense Acquisition Management Framework. As we started working with more organizations, however, we quickly realized that those organizations often used unique lifecycle models. As a result, we initiated an effort to create a lifecycle-independent version of the SAF, which we called SAF v0.2. We used Version 0.2 for our next pilot, which was focused on process improvement.

Process Improvement

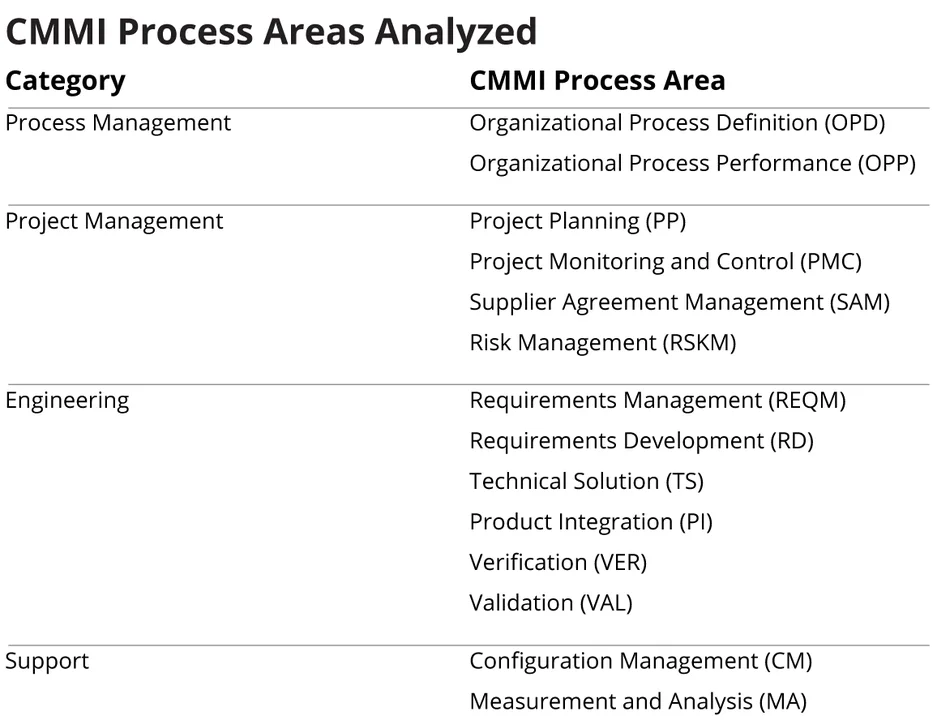

Our second application on the SAF involved a Level 5 CMMI organization that wanted guidance on integrating software security practices into its existing policies and procedures. For this engagement, we restructured SAF based on CMMI's structure. We grouped cybersecurity practices from SAF v0.1 into CMMI's four categories:

- process management

- project management

- engineering

- support

Each of the above categories comprises multiple areas of cybersecurity practice. In all, we defined 19 practice areas for the SAF v0.2, and documented cybersecurity practices for each area. The SAF features 76 cybersecurity practices across 19 practice areas.

For our customer engagement, we reviewed the organization's current policies, procedures, and templates for the CMMI process areas as detailed in the table below. After meeting with the organization's technical staff, we jointly determined that most of the organization's policies could remain unchanged since they were written from a sufficiently broad perspective. We did recommend that the organization consider creating a new policy for cybersecurity, which would identify roles and responsibilities for cybersecurity, define cybersecurity policy, and provide pointers to related cybersecurity procedures.

Based on our analysis of the organization's procedures and templates, we recommended several changes. In this blog, we focus on one of our suggestions--updating the organization's Requirements Development (RD) procedures. Here, we suggested that the organization develop a separate procedure for developing security requirements. Methods for eliciting security requirements typically combine security risk analysis techniques with standard requirements specification techniques. For example, the SEI Security Quality Requirements Engineering (SQUARE) method defines a means for eliciting, categorizing, and prioritizing security requirements for software-reliant systems and applications. We recommended that the organization adopt an approach for specifying security requirements (either SQUARE or an equivalent) and develop a procedure based on the selected approach.

While we suggested that the organization create a stand-alone procedure for developing security requirements, we did not see the need to make changes to its existing procedure for Requirements Management (REQM). The procedure for Requirements Management was sufficiently broad and could be used to manage all types of stakeholder and technical requirements, including security requirements.

Metrics

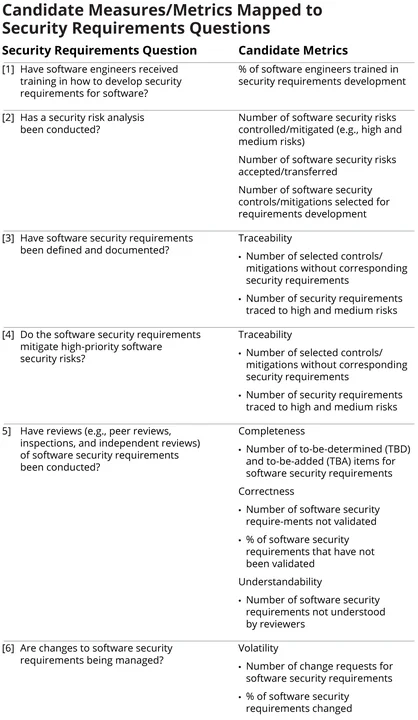

For our third application of the SAF, we used version 0.2 to generate a candidate set of engineering metrics for a DoD organization. We used a standard software engineering method, Goal-Question-Metric, to identify a candidate set of engineering metrics.

We worked with the organization's senior managers to identify the following organizational goal for software assurance: Supply software to the user with the acceptable software risk. Using that goal and the definition of software assurance, we identified two sub-goals:

- sub-goal 1: Supply software to the user that functions in the intended manner.

- sub-goal 2: Supply software to the user with a minimal number of exploitable vulnerabilities.

We then decided to focus on sub-goal 2 for our engagement with the organization. We used the SAF as the organizing structure for developing GQM questions. For example, we developed the following question for the Engineering category:

Do engineering activities minimize the potential for exploitable software vulnerabilities?

We then developed a question for each practice area in the engineering category of the SAF:

- Product Risk Management: Does the program manage cybersecurity risk in software components?

- Requirements: Does the program manage software security requirements?

- Architecture: Does the program incorporate appropriate cybersecurity controls in its software architecture and design?

- Implementation: Does the program minimize the number of vulnerabilities inserted into the code?

- Verification, Validation, and Testing: Does the program test, validate, and verify cybersecurity in its software components?

- Support Tools and Documentation: Does the program develop tools and documentation to support the secure configuration and operation of software components?

- Deployment: Does the program consider cybersecurity during the deployment of software components?

We also provided an example of the candidate metrics that we developed for the Requirements areas of the SAF. The table below contains the specific questions we generated for requirements and the candidate metrics we identified for each question.

We continue to work with this organization to select an initial set of engineering metrics from the list of candidates. The organization will then begin using the selected metrics to support its program management and decision-making activities.

Wrapping Up and Looking Ahead

As the pilots above illustrate, the SAF proved to be a useful tool in our three engagements. The framework provided us with a basis for describing, assessing, and measuring an acquisition program's cybersecurity practices. During each pilot, we used the SAF as a touchstone for our analysis activities.

It is important to emphasize, however, that we consider the SAF to be a working prototype. Each field application of the SAF has provided important insights about how we can improve the framework. We have already made changes to the framework based lessons learned from our three pilots. We will continue to update the SAF as appropriate based on the results of future pilot activities.

Our goals with this blog post and our recent technical note are to (1) raise awareness of the SAF in the software assurance and cybersecurity communities and (2) initiate a dialogue for refining and transitioning this work to practitioners in those communities. We do not consider the SAF to be a completed piece of work; rather, we view it as a "living" framework that we intend to nurture and grow in the years ahead.

We welcome your feedback on our progress thus far in the comments section below.

Additional Resources

View the SEI technical note Prototype Software Assurance Framework (SAF): Introduction and Overview.

Get updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedGet updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed