Three Approaches to Adding Flexibility in Software Sustainment Contracting

At the SEI we have been involved in many programs where the intent is to increase the capability of software systems currently in sustainment. We have assisted government agencies who have implemented some innovative contracting and development strategies that provide benefits to those programs. The intent of the blog is to explain three approaches that could help others in the DoD or federal government agencies who are trying to add additional capability to systems that are currently in sustainment. Software sustainment activities can include correcting known flaws, adding new capabilities, updating existing software to run on new hardware (often due to obsolescence issues), and updating the software infrastructure to make software maintenance easier.

The SEI works with government agencies to help them with a wide range challenges in sustainment including the following:

- Upgrades can be software-only, which can sometimes drive a direct relationship with a company that may have been a subcontractor on the original development.

- Some sustainment efforts upgrade obsolete hardware that cannot be maintained, but upgrades to hardware and infrastructure software (such as operating systems) often cause issues with the operational software.

- Other sustainment efforts are aimed at adding or improving cybersecurity, and these also can have large impacts on the operational software.

- Concurrent efforts in development and sustainment can often lead to complex configuration management challenges.

- Most organizations find that software updates after the system enters the sustainment phase simply don't fit the sustainment model and require patterns of engineering and development behavior that are more common during software development.

Often, after personnel who worked on the original development of the system move on to the next project, there is a shift in lead organizations (both in the government and the contractor) with different personnel responsible for sustainment. The bottom line is that software continues to evolve throughout the system's life and programs have discovered that they must consider continuous software engineering, development, integration, and deployment until the system is retired.

The following innovative approaches to the challenges of continuous software engineering, development, integration and deployment have been successfully used by production DoD acquisition programs. These innovations are not mutually exclusive, and can be used in combination as the needs of the individual program dictate.

1. Stagger the design and development work

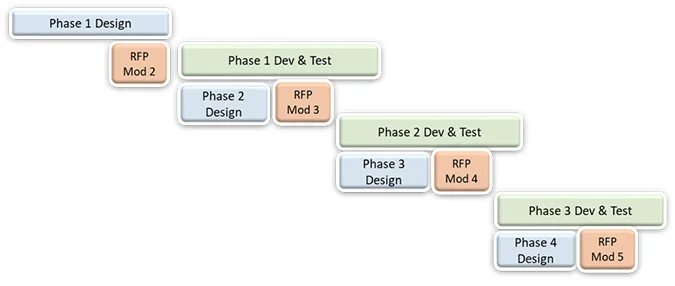

One idea is to stagger the design and development efforts by contracting for the development and test for the current phase in the same contract action as the design for the next phase. The pattern looks something like the figure below:

This approach works best when the capability requirements are planned out over several separate increments and/or the desired capability can be determined at least for the next phase. The first instantiation of this approach would be a special case, but after that a predictable pattern is followed. The SEI assisted a DoD program that implemented this approach. This program now releases a new software version every 12 months. This program implemented this approach via contract mods on a pre-existing contract, but this could also be implemented using a new contract with separate contract line item numbers (CLINS) for cost plus and firm fixed price if desired.

Advantages. One advantage to this approach is that the design work is complete prior to bidding on the development and test portion of the work, so the proposal estimates for development and test are more mature. The development and test work might even be appropriate for a firm fixed price (FFP) contract depending on the overall contracting mechanism and the work to be accomplished. A second advantage is that this approach provides more flexibility to the contractor to move staff between design and development work as needed and to ensure that personnel who mainly work on design are still available when the development and test work is being accomplished.

Disadvantages. Although moving staff between design and development as needed could provide flexibility to the contractor, it could have the unintended consequence that the staff working on the design for the next phase could be pulled away to help with the development and test work for the current phase, if that work runs into issues. This migration could then impact the completion date of the design work, which could impact the schedule for the request for proposal (RFP) and the technical evaluation for the next increment.

Another potential disadvantage is that the government program office must track and stay aware of both the design and development/test activities simultaneously, which can be hard in program offices that are not staffed to support this level of effort. This challenge of managing multiple baselines may also be felt by the user community depending on their resources and level of involvement.

2. Allow room in the contract for adding emerging requirements

Another idea that can help acquisition programs is to allow room in the development phase to add emerging requirements or to make corrections later in the development cycle based on user inputs. Many programs find that there are some changes in requirements as the design emerges and the implications of the design are better understood. While allowing for changing requirement priorities is a fundamental premise in Agile development, this can be accommodated in more traditional software development lifecycles by building extra capacity into the contract.

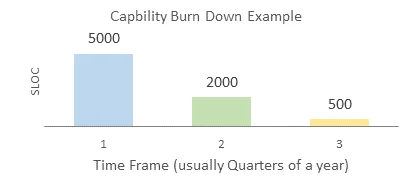

The extra capacity outlined above can be added to the RFP by requesting the proposal include "surge" options or contract "margin" that is scoped based on the format that is used for the overall software development estimating effort (extra lines of code (LOC), story points, function points, etc.). This surge or margin should include a "burn-down" schedule that allocates resources across the development phase. In addition, a clear approval process is needed to ensure additional scope is carefully managed and can't be added to address issues associated with poor estimation of the effort required to support the base effort (as was seen in one program).

The approval process described above would also help insure that the additional scope is not used so late in the development process that it adds too much complexity to the integration and test activities (as was seen in another program). The additional capability included could be a percentage of what is being developed, or it could be based on additional features desired, if this is known. The burn-down plan might look something like the graphic below.

Depending on how this method is used, it is important that the government and the contractor have established reliable communications and trust. The government and the contractor must develop a mutual understanding of what can be reasonably added to existing work at a given point in an effort. The SEI observed this use of margin in a government program, and it was very effective in allowing additions either due to new user priorities or issues found during operations after the start of code development for the next increment. Another possibility that could be used in both agile and non-agile developments would be to plan for a "catch-up" increment near the end of the development cycle that would be exercised at the discretion of the government.

Advantages. This approach provides a mechanism to add a limited amount of new capability to an existing effort without the need for an engineering change proposal and /or contract modification. One government program (and their contractor) that we worked with found that having a specific burndown plan made it clear that the scope of changes become limited later in the development cycle.

Disadvantages. By allowing room in the contract for emerging requirements, this approach increases the overall price of the effort being negotiated, which is sometimes an issue. Providing for margin in a firm fixed price contract would encourage the government to use all of the extra capability since the additional requirements are already paid for. Contractors, on the other hand, would be inclined to resist new requirements since any cost underruns belong to them, which could lead to disagreements. A better choice might be to break down the added capability into separate options so they could be executed as needed.

Another possible disadvantage is that the government may not adequately prepare prior to releasing an RFP for the next increment because they know that requirements changes can be accommodated after contract award. This concept was developed to allow issues found in operational testing or operations to be added to the current increment if possible and was not meant to allow for inadequate planning. Too much flexibility used up front to refine requirements can cause costly overruns later in the test phase.

3. Consider the use of Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contracts

Many SEI customers are moving toward the use of IDIQ contracts for sustainment efforts. The SEI has assisted customers in writing RFPs for IDIQ contracts, in writing task orders, and during task order execution. These contract vehicles are based on an overarching performance work statement (PWS) that outlines the overall work that can be done under the contract.

The price of a basic item is negotiated in the award of the IDIQ. This basic item is often a table of labor categories and costs (for level of effort type awards), but the basic item could be a development iteration (Agile sprint) or increment, or any other basic building blocks that can be composed to describe the work required to deliver the capabilities in the PWS. When defining these basic items in the IDIQ, the government must carefully consider what basic items will be ordered: possibly a mix of level-of-effort type tasks, releases of specific capabilities through iterations or increments (either agile or non-agile), studies, or a combination of these.

When specific work is desired, a task order (or delivery order) is written describing the specific work requested. The contractor delivers a proposal based on the task order and estimates the cost of the task order based on the number of basic items required at pre-negotiated rates. The government performs a technical evaluation and then negotiates the basic items needed with the contractor. Depending on the structure of the overall IDIQ contract, task orders can usually be written as either FFP or cost Plus (CP) (or even separate CLINS to include both FFP and CP in the same order) depending on the effort.

The IDIQ can be either a multiple-award contract or a single-award contract. In a multiple-award more than one contractor is award a contract and task orders are competed among those contractors. In a single award, one contractor is awarded the contract and the task orders are sole source awards.

Advantages. Individual task orders can be tailored to address the specific effort to be accomplished. It is often hard to know all the upgrades that may be needed (and funded) during a multi-year sustainment contract when the RFP is written. The IDIQ approach allows for greater definition and scope negotiations later in the contract.

Another advantage of this approach is that if there are issues with a contractor's performance, or a determination that no further improvements are necessary, there is no requirement to award any further task orders after the minimum identified in the RFP. This is a double-edged sword, of course, in that it may be necessary to start a new acquisition to enhance future software capabilities, but it does limit the government's liability in the face of program changes or poor contractor performance.

If a multiple award IDIQ is used, there are advantages based on continued competition for each task order, which can lower the cost of any individual task order. Competition for future orders could also influence the contractor's performance on the current effort if incentives are developed that allow for performance on previous orders to be considered when awarding new task orders. A caution: on a multiple award IDIQ the government must think carefully about the implications of different contractors delivering different increments of capability. The roles for architecture, integration, and test may have to be more stable to allow for different developers. Some programs have awarded these types of tasks to a single contractor who is then unable to bid on development efforts. In other programs, we have seen the government take on these roles.

Disadvantages. One disadvantage of using IDIQ contracts is that the RFP preparation can be more time consuming. The PWS must be well thought out to include possible tasks that cover future scope. In addition to evaluating the basic proposal against the PWS, one or more task orders must be developed and evaluated during the source selection. Some programs have developed both the order to be awarded with the IDIQ contract as well as sample task orders. Contractors then bid to the sample orders which allows the government to better understand the potential costs and risks.

Another disadvantage is that unless the government program office can develop an effective process and rhythm for writing task orders and evaluating proposals for the task orders these can take a lot of time and effort on the part of the government. Discussing the RFP with the contractor(s) in advance of the RFP release shortens the timelines and ensures there is a common understanding of the work being requested.

Looking Ahead

Investigation of the challenges and possible approaches to the continuous software improvement through the life of a system, particularly a weapon system, is an active area of research at the SEI. I welcome inputs and personal experiences from personnel who have worked on these programs. Please leave feedback in the comments section below.

Additional Resources Read other blog posts detailing the SEI's work in software sustainment.

Get updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedGet updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed