10 Steps for Managing Risk: OCTAVE FORTE

PUBLISHED IN

Enterprise Risk and Resilience ManagementTo ensure that risk management is effective, organizations need adaptable, agile frameworks that provide executives with a real-time view of cyber risks, and the related tools and processes they can use to address appropriate risks. Organizations should use enterprise risk management (ERM) principles, tools, and processes to understand and prioritize complex risks that compete for organizational resources.

The SEI developed OCTAVE FORTE, a process model that helps organizations evaluate their security risks and use ERM principles to bridge the gap between executives and practitioners. OCTAVE FORTE helps organizations new to risk management (i.e., nascent organizations) and organizations already familiar with risk management (i.e., mature organizations). This post, adapted from a recently published technical note, outlines OCTAVE FORTE's 10-step framework to guide nascent organizations as they build an ERM program and mature organizations as they fortify existing ERM programs, making them more reliable, measurable, consistent, and repeatable.

Establishing an ERM Framework

OCTAVE FORTE identifies processes that support the achievement of strategic objectives, including ways to help executives and practitioners effectively communicate threats and opportunities across the organization that relate to those objectives. It helps organizations establish an ERM framework that scales to the organization's size and strategy with limited overhead.

FORTE's 10 steps help an organization:

- understand its assets, capabilities, and risks

- form risk appetite statement(s) to document its risk tolerance

- create response plans to manage risks

- form processes to monitor whether risk is being managed effectively

- develop a plan to improve the organization's ERM program

FORTE benefits all levels of the organization. Executives use information about risk to develop a governance structure, prioritize risks, make informed decisions, allocate resources, and communicate risks using a tiered governance structure. Managers--including chief information security officers (CISOs), risk managers, and other organizational leaders in both private and public sectors--use elements of FORTE to identify and manage risk in their divisions and departments. Practitioners learn to apply their subject matter expertise in a way that enhances their analysis and helps them communicate their greatest concerns to management.

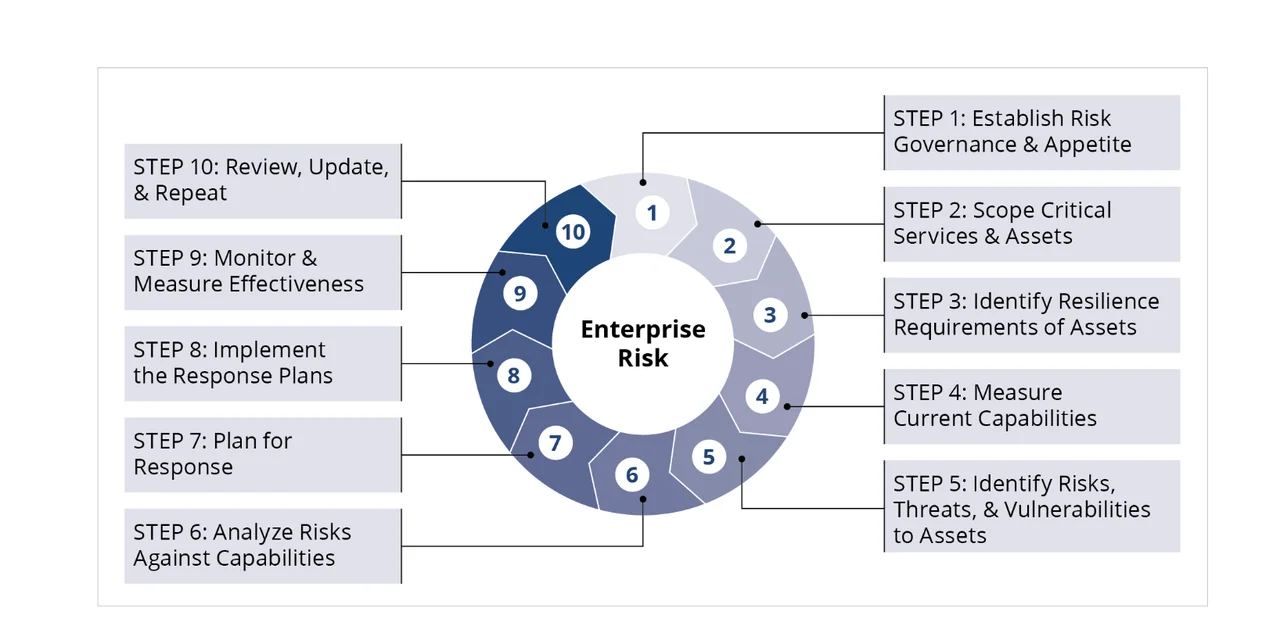

Figure 1 below depicts a high-level view of FORTE's 10 steps, which the remainder of this post will detail. For a deeper dive on each step, see the technical note from which this post has been adapted.

Step 1: Establish Risk Governance & Appetite. In this step, the organization asks itself, "How do I begin?" To accomplish this, the organization establishes a governance structure, determines how much risk it's willing to tolerate, and sets policies for how it manages risk.

Since FORTE is designed for the entire organization, the ERM governance structure should have guidance about roles, responsibilities, policies, resources, and information flow.

Risk governance can be thought of in different ways. For example, NIST SP 800-39, Managing Information Security Risk: Organization, Mission, and Information System View, describes a three-tiered approach to addressing risk across an organization:

- Tier 1 addresses risk at the organizational level by establishing and implementing governance structures that are consistent with the strategic goals and objectives of organizations and the requirements defined by federal laws, directives, policies, regulations, standards, and missions/business functions.

- Tier 2 addresses risk from a mission/business process perspective by designing, developing, and implementing mission/business processes that support the missions/business functions defined at Tier 1.

- Tier 3 addresses risk from an information system perspective. In addition to the risk management activities carried out at Tier 1 and Tier 2, risk management activities are also integrated into the system development lifecycle of organizational information systems at Tier 3. The risk management activities at Tier 3 reflect the organization's risk management strategy and any risk related to the cost, schedule, and performance requirements for individual information systems supporting the mission/business functions of organizations.

FORTE embraces this three-tiered approach, especially by recognizing that Tier 1 should focus on strategic risk (i.e., those risks that threaten the achievement of strategic objectives), while Tiers 2 and 3 should focus on more tactical risk (i.e., those risks that threaten everyday operations).

The organization must define its risk appetite and develop a risk appetite statement. A risk appetite is the general amount and type of risk that the organization is willing to take to achieve its strategic objectives [ISO 2018]. An organization's risk appetite statement articulates its risk appetite, and it should be periodically reviewed and updated as needed.

Step 2: Scope Critical Services & Assets. In this step, the organization asks itself, "What keeps us in business?" As part of this step, the risk manager plans for asset management, identifies and documents assets, and maintains the asset catalog.

Planning is the most critical task of the asset management process. Whether or not the organization uses FORTE to manage assets, its executives must require that critical assets are identified and documented in an asset catalog. They also must provide the funding, oversight, and staffing necessary to operate a comprehensive asset management program.

The organization must identify its assets--particularly its critical assets--and document them in an asset catalog. As part of this process, risk managers define the information to be gathered about each asset, including the level of detail. The level of detail can be challenging when describing data-related assets.

Regardless of which tool the organization uses to track assets, risk managers must ensure that the organization maintains the catalog. This maintenance might include identifying events that require updating asset records (e.g., preventive maintenance, repairs, replacement, age, change of use).

Step 3: Identify Resilience Requirements of Assets. In this step, the organization asks itself, "What do we need to keep our assets resilient?" For each asset in the organization's asset catalog, the risk manager identifies and documents resilience requirements and identifies how the organization will review these requirements.

Step 2 described the importance of identifying which assets to document and manage throughout their lifecycle. Resilience requirements are similar to asset requirements because the organization must identify and document resilience requirements for each asset in its asset catalog.

To identify resilience requirements, the organization evaluates its cybersecurity risk and defines how risk events can affect the assets in its asset catalog. In particular, it evaluates how these risks affect confidentiality, integrity, and/or availability (CIA); the loss of CIA can negatively affect organizational assets and services.

Step 4: Measure Current Capabilities. In this step, the organization asks itself, "What measures are currently in place?" The risk manager reviews the organization's existing controls, assesses control effectiveness, and creates a prioritized list of controls. Step 4 is part of an iterative process; it establishes baseline controls when FORTE is first applied and when updates to those baseline controls are made for each iteration thereafter.

To understand the organization's controls and capabilities, the risk manager should do the following:

- Review the organization's existing controls. For example, from a United States federal government perspective, these controls can be provided by the organization's system security plan, as prescribed by NIST SP 800-30.

- Determine whether the organization's existing controls meet the resilience objectives established in Step 3.

- Investigate whether additional research is necessary to identify all the risks. (Risks can extend beyond the cyber domain or the technical controls found in the organization's software. The risk manager must consider the organization's physical and administrative controls as well.)

- Consult with stakeholders to get additional information about the organization's assets, such as the rationale for the organization's control-related assets. (This rationale also helps the risk manager prioritize the controls as part of creating the list of controls.)

The risk manager must assess the effectiveness of the organization's existing controls, and can start by answering the following questions:

- Are the existing controls meeting the objectives established in Step 3? How do you know?

- Are all applicable compliance requirements handled sufficiently by controls? If not, can current controls be modified to address compliance requirements?

- Do the current controls satisfy the organization's crucial objectives? If not, does the organization's risk appetite justify overlooking the gap?

- Are there gaps where a service objective is not adequately satisfied by a control? If so, can current controls be modified?

- What is the most cost-effective option to satisfy the organization's objectives?

The risk manager must then use the above information to create a prioritized list of controls by setting targets for performance based on the organization's strategic objectives, risk tolerance, and service/asset resilience requirements and prioritizing control objectives.

Step 5: Identify Risks, Threats, & Vulnerabilities to Assets. In this step, the organization asks itself, "What could possibly go wrong?" The risk manager considers how the organization is affected by changes, such as shifts in technology, evolving environments, fluctuating market conditions, and new attack tactics. The organization builds on its asset catalog by examining its critical assets and documenting their associated risks, threats, and vulnerabilities.

The risk manager elicits information about risks by asking stakeholders to do the following:

- Review the organization's critical services and the assets that contribute to providing each critical service.

- List the threats and vulnerabilities related to each asset or asset category. (Keep in mind that risks can also be opportunities that may have positive outcomes.)

- Identify impacts that would result if each identified risk becomes a reality. (This task helps the organization gauge the "pain it will feel" if the asset or service is unavailable. Explore impacts by conducting a value stream mapping exercise.)

- Forecast the likelihood of each threat or opportunity becoming a reality. (Characterize the likelihood using measures such as high, medium, and low at the very least.)

- Analyze the consequences of impact. (Use the organization's risk appetite statement to help with this task.)

- Record these findings in the risk register and asset catalog where applicable. (In this step, Step 5, the risk manager conducts a form of risk identification and qualitative analysis. Although the risk manager builds a risk register as part of Step 6, this is where the roots of the register start to form.)

The organization's governance structure must advocate for risk management that is iterative and continuous, with the ultimate goal of instilling a risk culture throughout the organization. Risk management requires the organization and its members to continuously be aware of risks, prioritize them, and deal with their effect on the organization.

Step 6: Analyze Risks Against Capabilities. In this step, the organization asks itself, "Where do our current measures fall short?" The risk manager works with stakeholders to analyze the organization's risk data and create a risk register.

To analyze risk, the risk manager works with stakeholders to review the organization's risk appetite statement and analyze the organization's risks. However, risk analysis is subjective and rarely dictates what the organization must do or how its executives should allocate resources. Instead, risk analysis identifies the risks that represent the largest risk exposure for the organization in terms of impact and likelihood.

The risk manager and stakeholders do the following to analyze risks:

- Mine the Data. Controls (e.g., firewalls and anti-malware systems) are important sources of data that inform the risk analysis process. Part of mining data involves comparing the data from the organization's current controls to the organization's risk appetite statement to analyze which solutions are working well and which ones could be improved.

- Determine the Impacts and Likelihood of Risk. Previous steps focused on identifying the organization's critical assets. Working with stakeholders, the risk manager determines the likelihood of risks being realized, but this task can be challenging.

- Plot Risks Against Current Capabilities. To help perform this task, the stakeholders and risk manager should conduct threat identification, vulnerability analysis, compliance requirements identification, supply chain risk management, governance, and incident management. The risk manager should select ERM software that closely aligns with the organization's goals and operational needs.

Using the organization's risk appetite statement and the results of risk analysis, the risk manager creates a risk register--an annotated list of the organization's risks in priority order.

Step 7: Plan for Response. In this step, the organization asks itself, "How do we respond to risks?" So far, the FORTE process has focused on identifying and analyzing risks to identified assets and services. Knowing how the current controls compare to the organization's risks, the organization begins forming response plans. To accomplish this, the risk manager must educate stakeholders on how to develop response plans, identify interdependent risks, gather governance support, and maintain response plans.

A response plan predetermines what the organization will do to reduce risk and respond to risk when it becomes an issue. Response plans seek to disrupt, reduce, or avoid the following:

- risk triggers from taking place

- consequences from making meaningful impact

- alignment of conditions that would allow risks to become a reality

Risks don't operate in a vacuum; they often interact or affect one another, and when they do, they're called interdependent risks. If interdependent risks become issues, the consequences can initiate a ripple effect across the organization and affect operations. Before writing a response plan, the risk owner must realize that risks can be interdependent. The risk manager or analyst must comb through input from the risk owners about their risks to identify interdependent risks, which the risk manager leverages and uses to develop a response plan.

Every response plan must incorporate a compelling business case because it needs to persuade the governance structure to provide resources to implement it and its related projects. In particular, the risk manager must capitalize on responding to risk interdependencies by constructing the business case for responding to these risks in the response plan for interdependent risks to provide a better return on investment.

Step 8: Implement the Response Plan. In this step, the organization asks itself, "How do we ensure that our responses reduce overall risk exposure?" The risk manager ensures that the governance structure allocates resources to implement the response plans, the organization forms projects to implement the plans, and project managers measure and report performance.

The risk manager is responsible for ensuring that the organization implements its response plans. The first part of doing that is ensuring that the governance structure allocates resources to the response plans and their projects to enable that implementation.

The organization must plan and form projects to execute the work outlined in the response plans. Who establishes and performs projects varies depending on the organization. The organization might have a policy or process that mandates how projects are formed; if not, the governance structure must appoint someone who has the authority, responsibility, and resources to implement the plan and coordinate the work.

Projects must have the following characteristics:

- have a project plan that includes its scope, schedule, budget, requirements, and risks

- establish and measure success criteria

- set milestones toward project completion

- be assigned to a project manager who leads the project and is responsible for its operation and completion

To report on the performance of their projects, project managers should consider using schedule performance index (SPI) and cost performance index (CPI) metrics. Since the organization is likely to have many response plan projects, SPI and CPI metrics provide a normalized means of comparing projects and assessing the overall effectiveness of the organization's risk response.

Step 9: Monitor and Measure for Effectiveness. In this step, the organization asks itself, "How effective is the ERM program?" With FORTE, the organization uses measurement to keep informed of the effectiveness of the organization's ERM program. In FORTE's Steps 2-8, the organization focused on identifying risks, vulnerabilities, and threats to its critical assets and services. It then formed plans to respond to the identified risks. In Steps 9 and 10, the organization shifts gears to evaluate its ERM program. To accomplish Step 9, organizations must define metrics to measure the right things, measure the ERM program's effectiveness, and monitor risk exposure and impact.

To identify metrics, the risk manager starts by determining which risk-related results and progress can be measured. In a cybersecurity organization, examples of these kinds of measures include the following:

- the percentage of employees who responded to a test phishing campaign before and after implementing a training program

- the percentage of employees who entered their credentials before and after a system was changed to use multifactor authentication

- the percentage of employees who reported test phishing emails to IT security before and after a new standard procedure was added to the IT security policy

Metrics help the risk manager evaluate how well the ERM program is doing by monitoring the following metrics in an order of precedence most relevant to their program and organization:

- Response plan implementation. Monitoring the progress of implementing response plans helps the organization track the progress of the teams involved. Implementation issues may be specific to a project or indicate a problem in the overall ERM program.

- Risk exposure. Monitoring the organization's risks as they begin to be realized shows how improvements have affected the organization's risk exposure. Measuring and responding to key risk indicators (KRIs) is a way to accomplish this kind of monitoring. By monitoring KRIs, risk owners and managers are notified that a risk may be turning into an issue.

- Impacts from risk exposure. Monitoring the impact from risk exposure provides critical feedback that the organization should use to improve its risk appetite statement and risk register. For example, if an impact is less than expected, the priority of the risk may change. If an impact involved unexpected parts of the organization, stakeholders from that part of the organization should be included when the improvement plan for that particular risk is being updated. The risk manager should conduct post-event reviews to understand how response plans, disaster recovery plans, and business continuity plans affected that risk exposure.

Step 10: Review, Update, and Repeat. In this step, the organization asks itself, "Is our ERM program successful?" With input from the Tier 1 leaders of the organization's governance structure, the risk manager reviews and evaluates the ERM program's effectiveness, develops the improvement plan, implements the improvement plan, and repeats the FORTE process. How often the organization conducts these reviews depends on factors such as the organization's risk appetite and the maturity of its ERM program.

The risk manager should prepare questions to ask stakeholders, such as asset owner and risk owners, about whether the ERM program is operating the way it should. Example questions include the following:

- How well did ERM policies and procedures support related activities?

- Was the method the ERM program used to select metrics for measuring the organization's risk exposure effective?

- When resources were needed, was it clear whom to talk to?

- Were the right committees and subcommittees named to support the ERM program?

The risk manager develops and writes the improvement plan for the ERM program to increase its maturity and improve its performance. Typically, these plan activities require resources and comprise the elements of the ERM program. The improvement plan should address

- investment

- training

- communication

- policy changes

- contingency planning

- organizational changes (e.g., new teams)

- asset procurement

Once the improvement plan is generally accepted, the risk manager coordinates with the governance structure to secure the resources needed to implement the plan.

It is important to remember that risk management is ongoing, so the organization's ERM program is always a work in progress. As the organization improves its ERM program and reduces risk exposure and impact, it also improves its ability to continually evaluate its operation and make improvements. The ERM program is not finished just because the organization completes a cycle of risk management; in fact, it is never finished.

Additional Resources

Download the SEI technical note, Advancing Risk Management Capability Using the OCTAVE FORTE Process. For more information about OCTAVE FORTE or how to start using it in your organization, contact info@sei.cmu.edu.

View the SEI Webcast, Risk Management for the Enterprise-How Do You Get Executives to Care About Your Risks? with Brett Tucker and Matthew Butkovic.

More By The Author

More In Enterprise Risk and Resilience Management

Process and Technical Vulnerabilities: 6 Key Takeaways from a Chemical Plant Disaster

• By Daniel J. Kambic

PUBLISHED IN

Enterprise Risk and Resilience ManagementGet updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedMore In Enterprise Risk and Resilience Management

Process and Technical Vulnerabilities: 6 Key Takeaways from a Chemical Plant Disaster

• By Daniel J. Kambic

Get updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed