API Hashing Tool, Imagine That

PUBLISHED IN

CERT/CC VulnerabilitiesIn the fall of 2018, the CERT Coordination Center (CERT/CC) Reverse Engineering (RE) Team received a tip from a trusted source about a YARA rule that triggered an alert in VirusTotal. This YARA rule was found in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Alert TA17-293A, which describes nation state threat activity associated with Russian activity. I believed this information warranted further analysis.

The YARA rule, shown in Figure 1, is allegedly associated with the Energetic Bear group. The Energetic Bear group, named by security firm CrowdStrike, conducts global intelligence operations, primarily against the energy sector. It has been in operation since 2012. (For more information, see CrowdStrike Global Threat Report: 2013 Year in Review.) This group has also been referred to as Dragonfly (Symantec), Crouching Yeti (Kaspersky), Group 24 (Cisco), and Iron Liberty (SecureWorks), among others. (For more information, see APT Groups and Operations.)

Figure 1: YARA Rule for DHS Alert TA17-293A

Unfortunately, upon reviewing numerous public threat reports from the above vendors, I could not find further information tying this YARA rule or associated exemplars to the Energetic Bear group, but I still believed that the activity warranted further investigation and analysis.

Methodology

I used the following methodology for this analysis:

- analyzed the YARA rule and initial exemplar

- analyzed exemplar with IDA

- researched and applied API hashing module routine findings to exemplar

- mapped research findings and analysis to exemplar with IDA

- created a tightly scoped YARA rule to discover new exemplars

- created API hash YARA rules to discover more exemplars

- analyzed new exemplars with refined YARA rule

- created a tightly scoped YARA rule

- discovered API hashes found in new exemplars

- questioned attribution

- identified future work

- reported results

Analyzed the YARA Rule and Initial Exemplar

I was interested in understanding the string variables found in the YARA rule shown in Figure 1. Specifically, it was not immediately clear what the $api_hash variable represented, whereas the variables $http_post and $http_push appeared to be associated with Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) header fields. I focused my analysis on the $api_hash variable.

Analyzed Exemplar with IDA

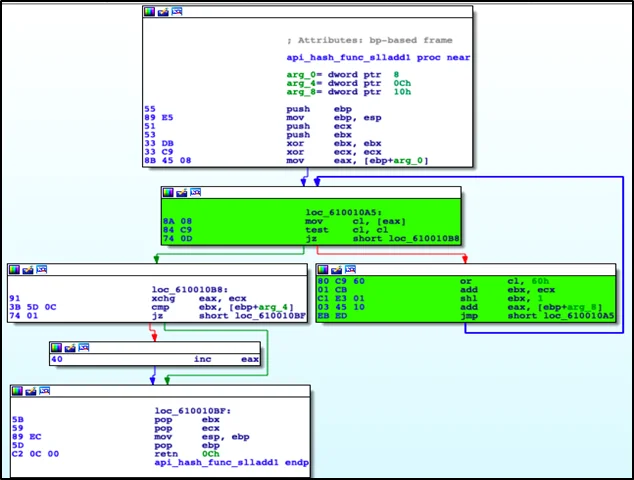

After cursory analysis of the initial exemplar (SHA256: 1b17ce735512f3104557afe3becacd05ac802b2af79dab5bb1a7ac8d10dccffd), I determined that the $api_hash variable was alerting on the routine (highlighted in green in Figure 2).

Researched and Applied API Hashing Module Routine Findings to Exemplar

The key points to highlight in Figure 2 are the or of 0x60, shift logical left (shl) by 1, followed by an add, and jump. Based on this information coupled with the variable name $api_hash, I was able to determine that this was a Windows application programming interface (API) hashing routine.

I wanted to find further information on any API hashing techniques. Through open source intelligence (OSINT) gathering, I discovered the FireEye Flare IDA Pro utilities Github page that mentioned a plug-in called Shellcode Hashes and an associated blog post from 2012 titled "Using Precalculated String Hashes when Reverse Engineering Shellcode," which further discussed API hashing. (For more information, see FireEye Flare IDA Pro utilities Github and Using Precalculated String Hashes when Reverse Engineering Shellcode.) After I examined the FireEye Flare IDA plug-in script further, I found it contained 23 API hashing modules. I identified an API hashing module, shown in Figure 3, that was very similar to the routine found in the exemplar shown in Figure 2. This API hashing module is a function that contains a for loop, which contains an or of 0x60 followed by add and a shift left by 1.

Figure 3: sll1AddHash32 Function from FireEye Flare IDA Plug-In

The CERT/CC has an API hashing tool that creates a set of YARA signatures of API hashes for a given set of dynamic link library (DLL) files. This API hashing tool contained 22 API hashing modules. One of these modules matched the routine from the exemplar shown in Figure 2 and the FireEye API hashing module shown in Figure 3. I called this API hashing module sll1Add. I used the CERT/CC API hashing tool and a clean set of DLL files (see Table 1), to create a set of YARA rules for the sll1Add routine. After running the entire set of YARA rules against the exemplar, I received an alert for kernel32.dll API hashes shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: API Hashes from kernel32.dll for sll1Add Routine

Mapped Research Findings and Analysis to Exemplar with IDA

I used another CERT/CC tool called UberFLIRT. UberFLIRT calculates and stores position independent code (PIC) hashes of arbitrary functions, easily shares information via a central database, and allows for fewer false positives than IDA's Fast Library Identification and Recognition Technology (FLIRT). I labeled the function shown in Figure 2 in IDA as api_hash_func_slladd1 and saved it to the Uberflirt database to facilitate future analysis of similar exemplars.

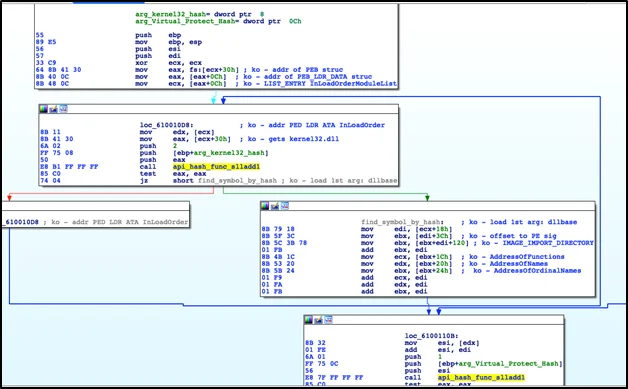

Examining the entry point of the exemplar, I found two values that are pushed onto the stack and passed as parameters to a function. These two values are 0x0038D13C and 0x000D4E88. The value 0x0038D13C is the hash of VirtualProtect shown in Figure 4. The other value, 0x000D4E88, is discussed below.

Examining this function, where the API hashes were passed as parameters, I determined that this exemplar uses manual symbol loading techniques, which are very similar to that of shellcode, to interact with the system through APIs.

This process reads the Thread Environment Block (TEB) to find the pointer to Process Environment Block (PEB) structure. The PEB structure is then parsed to find the DllBase of kernel32.dll. This exemplar also checks to ensure that it has the correct kernel32.dll by using 0x000D4E88 hash value to check for the kernel32.dll base name to the kernel32.dll that was found via manual symbol loading. The function then continues to parse the portable executable (PE) export data and passes the virtual protect hash (0x0038D13C) to the hashing algorithm. The same is done for the remaining hashes. This process is shown in Figure 5 with my added comments. I labeled the function from Figure 5 manual_symbol_resolution and saved it to the UberFLIRT database to aid in future analysis of similar exemplars.

Now that I understood the initial exemplar, I proceeded to find similar exemplars.

Created a Tightly Scoped YARA Rule to Discover New Exemplars

I used the following process to find additional exemplars:

- created API hash YARA rule to discover more exemplars

- analyzed new exemplars with refined YARA rule

- created a tightly scoped YARA rule

Created API Hash YARA Rule to Discover More Exemplars

The YARA rule, shown in Figure 6, represents the push of the API hash value (0x0038D13C), the push of the DLL base name hash value (0x000D4E88), and the call to manual_symbol_resolution.

I used the YARA rule, shown in Figure 6, to discover an additional 36 potential exemplars. To discover these files, I used the CERT/CC's large archive of potentially malicious software artifacts called the Massive Analysis and Storage System (MASS). The MASS is a distributed system designed to download, process, analyze, and index terabytes of potentially malicious files on a daily basis.

Figure 6: API Hashes

Analyzed New Exemplars with Refined YARA Rule

I refined the YARA rule from Figure 1, as shown in Figure 7, to further examine the potential 36 exemplars for the existence of the API hashing routine. I assumed that if additional exemplars contained the string variable from the YARA rule shown in Figure 6, then these exemplars should have the API hashing routine from the YARA rule shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Refined YARA Rule

Upon further analysis, I realized that some of the new exemplars did not alert with the YARA rule shown in Figure 7. I analyzed this subset of exemplars and discovered two slight variations in the API hashing routine. The first was an addition of one extra byte, while the second dealt with 64-bit files.

Created a Tightly Scoped YARA Rule

I refined the YARA rule further to incorporate these two additional variations shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Tightly Scoped YARA Rule with All Variations

This YARA rule, shown in Figure 8, could be refined further by combining the API hash routines into one string variable. However, when identifying new exemplars, I wanted to know which API hashing function was found in the exemplar.

Discovered API Hashes Found in New Exemplars

I turned my attention to identifying the sll1Add routine API hash values found in all of the 37 exemplars.

All exemplars had the sll1Add routine API hash values for functions from kernel32.dll. These are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: sll1Add Module API Hash Values from kernel32.dll

Most of the exemplars had the sll1Add routine API hash values for functions from ws2_32.dll, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: sll1Add Module API Hash Values from ws2_32.dll

There were a few outliers that had the sll1Add routine API hash values for functions from wininet.dll. These are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11: sll1Add Module API Hash Values from wininet.dll

The API hashes shown in Figures 10 and 11 indicate that these exemplars have potential network communications. I analyzed these exemplars to identify the network-based indicators of compromise (IOC). The use of two different DLLs for network communications points to the existence of at least two different versions of the API hashing tool.

I identified 29 unique IP address, including private IP space and port pairings, shown in Table 3, from 33 of 37 exemplars.

The other 4 of 37 exemplars had a structure outbound POST request. For 2 of these 4, I captured the requests in a packet capture (pcap) using FakeNet. I had to infer the outbound POST request structure from strings for the remaining 2 exemplars. These POST requests are shown in Figures 12 and 13. The strings of the POST request are shown in Figures 14 and 15.

Figure 12: Captured Network Communication from Exemplar (SHA256: 2595c306f266d45d2ed7658d3aba9855f2b08682b771ca4dc0e4a47cb9015b64)

Figure 13: Captured Network Communication from Exemplar (SHA256: 1b17ce735512f3104557afe3becacd05ac802b2af79dab5bb1a7ac8d10dccffd)

Figure 14: Network Communication Strings from Exemplar (SHA256: 34f567b1661dacacbba0a7b8c9077c50554adb72185c945656accb9c4460119a)

Figure 15: Network Communication Strings from Exemplar (SHA256: 9676bacb77e91d972c31b758f597f7a5e111c7a674bbf14c59ae06dd721d529d)

This information can be turned into signatures for network intrusion detection systems, such as Snort or Suricata.

Questioned Attribution

I attempted to identify other public reporting or research related to this Energetic Bear group API hashing tool. I did not identify any public reporting or research.

Because of the link to the Energetic Bear group, I thought the exemplars could be a remote access Trojan (RAT), such as Havex, which is also attributed to this particular group. I discovered research by Veronica Valeros on A Study of RATs: Third Timeline Iteration. I contacted her directly and ask if she recalled any of the RATs she researched using an API hashing technique. She could not recall, but mentioned that it could have been missed because she was not explicitly looking for this technique. I used her research to attempt to identify RATs that use this API hashing technique. I was unable to identify any publically reported RAT using this technique.

Identified Future Work

This brings me to a couple outstanding questions:

- Why is this API hashing tool linked to the Energetic Bear group?

- Who actually wrote the YARA rule from Figure 1 found in DHS Alert TA17-293A?

- Can the author of the YARA rule provide more insight to this problem?

I hope by publicly discussing this analysis that I can encourage information sharing and allow us, as a community, to engage in more detailed threat reporting.

Lastly, I have reached out to the MITRE ATT&CKTM team to ask for an additional technique, API hashing, to be added to its framework. During my analysis, I could not find this explicit technique listed in the framework.

Reported Results

I expanded the corpus of information from afore mentioned trusted partner regarding DHS Alert TA17-293A. This information includes

If the attribution and my research are correct, this may be the first publicly documented report of an API hashing technique being used by a nation state actor.

Updates

(May 3, 2019)

I've worked with the MITRE Malware Attribute Enumeration and Characterization (MAECâ„¢) team to have API Hashing added to the Malware Behavior Catalog Matrix. You can find the API Hashing listed as a Method under Anti-Static Analysis--Executable Code Obfuscation.

(March 27, 2019)

The power of open source sharing has been positive. It was brought to my attention (thanks to Matt Brooks from Citizen Lab) that this API hashing tool is related to Trojan.Heriplor from Symantec's Dragonfly: Westion energy sector targeted by sophisticated attack group report. The hash in Symantec's report is, in fact, one of the exemplars found shown in the appendix. Symantec provided this hash in the form of a picture, and I must have fat-fingered the hash when transcribing it. However, this specific API hashing technique isn't mentioned in their report.

This corroboration does help to answer my own question from the Identified Future Work section. Symantec's Trojan.Heriplor analysis attributes my analysis of this API hashing tool to Energetic Bear. More importantly, this linkage also shows that this tool is still actively used.

Appendix

List of Clean DLL Files Used to Identify API Hashes

Table 1: List of DLL Files

Hashes of Exemplars

Table 2: List of Exemplars SHA256 Hash Values

Identified Network Communications (Deduplicated)

Table 3: List of Identified Network Communications

PUBLISHED IN

CERT/CC VulnerabilitiesGet updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedMore In CERT/CC Vulnerabilities

Get updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed