System End-of-Life Planning: Designing Systems for Maximum Resiliency Over Time

It is fun to talk about new capabilities. Whether you are courting new customers, developing a new product, or expanding your research, there’s an element of excitement that comes with doing something novel. For engineers, there can be great joy in creating solutions to problems that no one has solved before. When you’re caught up in the excitement of rolling out new capabilities, it can be difficult to look into the future and consider ongoing operation and sustainment activities, not to mention the retirement of a service you haven’t even deployed yet. In this blog post, we advocate for the often-overlooked consideration of system retirements during the early planning and design phases of a computing-environment deployment. We look specifically at hardware replacements and decommissions and examine why your initial deployment plan should take these into consideration, even though such activities may not occur until years after your computing environment is deployed.

If you have been a system administrator for any amount of time, you will have inevitably had the discussion in which you have old equipment that is acting up and needs to be replaced, and you have gone to the system owner asking them what they want you to do about it. They then give you a look that seems to say, “What are you talking about? It is your problem.” Typically they want to hold on to whatever it is, squeezing the last electron of life out of it before it lets out the magic smoke. Or they assume that all the equipment is automatically upgraded from some overhead charge string that the company maintains. If you are lucky enough, they have budgeted for it, and now you are hoping that the system admin who set up the system five years ago planned for the upgrade, and that there is documentation somewhere. Otherwise, like Rumpelstiltskin, you might have to make gold from straw.

One of the key risks in operating a data center is failure of a mission caused by poor planning. In fact, the ongoing operational success of on-premises and co-located datacenter computing environments depends heavily on upfront planning and design activities. Neglecting to allocate the correct resources to a project in the planning phases can result in equipment failures, degradation of performance, extended downtimes, or total failure of mission-critical systems. All these outcomes demonstrate a lack of resiliency within a system.

In a recent SEI technical note, we stressed the importance of planning and design as a foundation for success of a computing-environment rollout. In that document, we provided a high-level set of considerations that are integral to a successful endeavor, based on SEI in-house experience and from consulting with organizations about their management of computing environments. Hardware replacement and decommission is an important addition to the considerations outlined in the technical note.

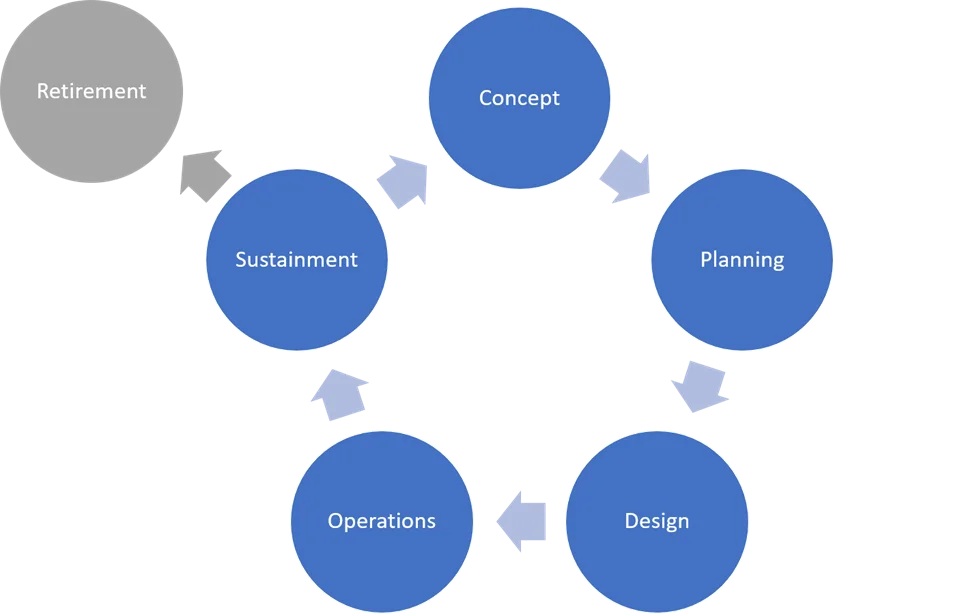

Computing Environment Lifecycle

The lifecycle of a computing environment comprises these stages:

- concept

- planning

- design

- operations

- sustainment

- retirement

Depending on what your business needs are, these stages can be linear or cyclical. For example, if you are deploying a computing environment to satisfy a time-bounded mission need, and after 18 months, the project funding will be exhausted and the computing environment will no longer be in use, your computing environment’s lifecycle will follow a linear model.

Alternatively, if you are deploying a computing environment to satisfy a long-term mission need, such as a development environment with long-term support for software projects, or a multi-tenant cloud environment where resources are used on-demand for multiple projects, your computing environment’s lifecycle will follow a cyclical model. You should expect to perform ongoing assessments of business and mission needs, which feed planning and design activities, inform acquisition and deployment procedures, and ultimately result in the operation and sustainment of some set of capabilities.

In this long-term operational scenario, you will need a plan for hardware replacements and decommissions.

Impact on Computing Environment

All physical hardware has a finite lifespan. Most manufacturers will sell hardware with three to five years of support and maintenance. Many vendors will offer extended support after that time, and there are even some third-party vendors that offer support beyond the timeframe that vendors will offer it. Eventually, however, the manufacturers of the hardware will stop making replacement parts. So even if you are trying to extract maximum usage from a physical system, at some point that system will be replaced or retired. In addition to the physical and mechanical limitations of hardware, vendors will also stop providing firmware updates, leaving your systems susceptible to attack due to unpatched vulnerabilities.

When replacing the hardware, you’re typically looking at migrating the services provided by that hardware to another physical system. Failure to plan and budget for replacement and decommissioning activities adequately can present several challenges and have a detrimental effect on the operation of your computing environment.

The first and most obvious impact is to your capital budget. To purchase new hardware, you’ll have to spend some capital. The amount of replacement hardware you’re able to purchase may be determined by your budget, and you’ll have to make decisions that prioritize the replacement of some mission-critical systems over others. Therefore, when accepting new projects into your datacenter, you need to account for the ongoing maintenance costs and have an agreed-upon timeline for decommissioning or replacing the hardware and a plan for how the replacement will be financed. When budgets are set annually, having a plan to pay for something five to seven years in the future may be difficult. If the project is suspended or canceled in three years, what happens to the equipment, and who pays for its decommissioning?

The replacement plan will affect how much hardware you can purchase during your initial deployment. When the time comes to replace your older hardware, you will need enough power, cooling, network, and physical capacity in your data center to support both the old and new systems for a period of time, so that you can deploy an operating system on the new server, install and configure the required software, and migrate data from the old system to the new, all while maintaining the availability of the capabilities of the old system. Your plan should account for your maximum resource capacity and ensure that your execution of the hardware migration stays below that threshold. In some cases, you may be forced to replace older hardware incrementally in stages to avoid exceeding some aspect of your computing environment’s capacity. Remember that this also needs to include any fail-over, redundancy, and disaster-recovery components that were in place on your old systems.

For example, if you completely fill your physical space during your initial deployment, when you procure new servers to replace your old servers, you won’t have any rack space available. If you exhaust your power and cooling capacity during your initial deployment, you won’t be able to power on your new servers to image and configure them. If you use all available switchports, you won’t be able to access your new systems remotely to configure them. Therefore, this surge in capacity must be accounted for in planning and design. This capacity surge may also affect your backup systems. If you want to test your backups on the new servers before cutting over from the old ones, your backup systems may be required to process and store both sets of data for a short period of time.

The process of migrating services from old hardware to new hardware must also be accounted for in your budgeting of operational costs, because your staff members will expend effort to deploy the new systems. If your operational staff is 100 percent occupied with the maintenance of your existing capabilities, the efforts spent on the migration processes will affect the availability of those capabilities.

When decommissioning old hardware, you’ll need to have a different plan. Ideally you will have already created a retirement plan giving budgetary and logistics requirements. Know what information and data is sensitive to your organization and how media containing that information is to be cared for and archived. Drives can be degaussed or shredded. Remember to also remove any sensitive data from the BIOS or firmware of disposed-of hardware. Incineration is another option for destroying sensitive data on hardware components. Hardware takes up physical space, so you need to be aware of your space limitations for storing physical systems no longer in use. There are outside organizations that recycle and dispose of old computer hardware.

Your retirement plan should have a final verification step that confirms that all the decommissioning steps have been completed successfully. These steps should

- Confirm that there are no detrimental effects following retirement. These might include open firewall ports, lingering account access, or other security-related items.

- Verify that any hosted tools or utilities have been properly decommissioned and any related contracts canceled.

- Verify that data archiving or destruction has occurred as planned. Pay particular attention to ensuring that access to data has been terminated and that any data preserved in backups is being handled according to the instructions documented during planning and in accordance with government regulation.

- Withdraw operating staff affected by the decommissioning of old hardware from the system or system elements and record relevant operating knowledge and lessons learned.

The Value of Foresight

Decisions made early in the planning and design phases of a computing environment’s lifecycle will have downstream effects on acquisition, deployment, operation, and sustainment activities. Making sound and reasoned decisions early greatly decreases the likelihood of encountering issues and blockers later. You can prevent future problems by being mindful of the long-term lifecycle of your computing environment during the earliest planning and design stages of the environment’s lifecycle. Anticipating at some level of detail the issues you’ll encounter in the future will help prevent emergencies and calamities. If you’re going to operate your computing environment for a significant amount of time, you’ll certainly retire and replace hardware, and being prepared with a plan for those activities will ensure that you’re simply operating as expected, and not scrambling to resolve outages or consume your budget on an unexpected expense.

Additional Resources

Read the SEI technical note, Planning and Design Considerations for Data Centers.

Read the SEI blog post, It’s Time to Retire Your Unsupported Things.

More By The Authors

More In Enterprise Risk and Resilience Management

Process and Technical Vulnerabilities: 6 Key Takeaways from a Chemical Plant Disaster

• By Daniel J. Kambic

PUBLISHED IN

Get updates on our latest work.

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe Get our RSS feedMore In Enterprise Risk and Resilience Management

Process and Technical Vulnerabilities: 6 Key Takeaways from a Chemical Plant Disaster

• By Daniel J. Kambic

Get updates on our latest work.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Subscribe Get our RSS feed